Can kangaroos fly?

Are there terrestrial mammals in New Zealand?

The nineteenth century palaeontologist Richard Owen standing next to the skeleton of a Giant Moa. The image is from Owen’s 1879 book Memoirs on the Extinct Wingless Birds of New Zealand (Image: Wikimedia Commons)... more

Yes, of course

Oh dear, get a grip. Perhaps you haven’t been there? The place is swarming with mammals, not least the air-line pilots who ferry thousands to and from New Zealand every day. True enough, but consider how they got there. There are indeed indigenous bats and seals, but the former flew to their new and isolated home, whilst seals (and penguins) could swim to the shores. Everybody else is a very recent immigrant. First the Polynesians, engaged in their extraordinary Pacific diaspora, and stepping ashore as Maoris at more or less the same time as Henry III reigned over England. Later, waves of Europeans, bringing in a host of mammalian companions – dogs, sheep, even hedgehogs – that collectively had a profound impact on the indigenous fauna and flora. So no shortage of terrestrial mammals, even though some have proved to be real troublemakers. Best known is the story, more a legend, of the lighthouse keeper’s cat polishing off the planet’s only representatives of the Stephens Island wren.

No, don’t be ridiculous

Please re-read the question; I said not just mammals but terrestrial mammals. While New Zealand is full of the ghosts of recently departed species like the Moa, there are much older hauntings. Fossil fragments from the Miocene of South Island appear to represent not only an indigenous mammal, but intriguingly one that appears to be neither a placental nor marsupial and maybe a holdover from the time of the dinosaurs. This find poses some fascinating questions. When and how did it arrive in New Zealand? When and why did it go finally extinct, so leaving a land without a single terrestrial mammal?

It all depends on the question

New Zealand represents a marvellous evolutionary laboratory, giving us a glimpse of how a world functions without terrestrial mammals. The indigenous mystacinid bats can still fly, but have converted themselves into mice-avatars. Tightly folding their wings they scuttle across the forest-floor, live in tunnels, and with acute hearing enjoy an omnivorous diet. The iconic kiwi is for all intents and purposes an honorary mammal, with fur-like feathers and a nocturnal life very much relying on its sense of smell. This bird is only one of a variety of ground-dwellers, of which the most spectacular was the Giant Moa. Now extinct, these enormous birds were briskly converted into moa-burgers and moa-twizzlers, not to mention moa-omelettes, by the incoming Maoris. So the Moa faced the same fate as innumerable other species on oceanic islands when the colonists arrived. Yet these birds left memories other than the stacks of bones and broken eggshells. The Moa was a browser but fed in a rather different way to its mammalian counterparts such as a cow or deer. To make life difficult for the Moa the plants adopted countermeasures. These included tough narrow branches with widely separated and small leaves or alternatively ensured those leaves growing in the browsing zone (which for a Moa is up to 3 metres!) are in one way or another difficult to spot. The Moa has vanished, but nobody told the plants.

Text copyright © 2015 Simon Conway Morris. All rights reserved.

Further reading

Antonelli, A. et al. (2011) Absence of mammals and the evolution of New Zealand grasses. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, B 278, 695-701.

Bond, W.J. et al. (2004) Plant structural defences against browsing birds: a legacy of New Zealand’s extinct moas. Oikos 104, 500-508.

Fadzly, N. and Burns, K.C. (2010) Hiding from the ghost of herbivory past: Evidence for crypsis in an insular tree species. International Journal of Plant Sciences 171, 828-833.

Galbreath, R. and Brown, D. (2004) The tale of the lighthouse-keeper’s cat: Discovery and extinction of the Stephens Island wren (Traversia lyalli). Notornis 51, 193-200.

Hand, S.J. et al. (2009) Bats that walk: a new evolutionary hypothesis for the terrestrial behaviour of New Zealand’s endemic mystacinids. BMC Evolutionary Biology 9, e169.

Lee, W.G. et al. (2010) Legacy of avian-dominated plant-herbivore systems in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 34, 28-47.

Wilmshurst, J.M. et al. (2011) High-precision radiocarbon dating shows recent and rapid initial human colonization of East Polynesia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 108, 1815-1820.

Worthy, T.H. et al. (2006) Miocene mammal reveals a Mesozoic ghost lineage on insular New Zealand, southwest Pacific. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 103, 19419-19423.

Can you see heat?

Enhanced infrared satellite loop of Hurricane Odile from September 2014 showing temperature fluctuations of the hurricane (Image: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Satellite Services Division via Wikimedia... more Commons)

No, don’t be ridiculous

“Let’s get this right. Did you say see heat, or just feel it? No question of the latter, very useful around the kitchen, thank you. But I feel the hot-plate, I don’t see the actual infrared radiation”. Of course lots of animals possess the capacity to sense heat, not in a general way but with considerable acuity that is central to their lives. Vampire bats and bed-bugs in search of a blood dinner, beetles and other insects flying towards forest-fires – no, no, not for suicidal self-immolation, but to lay their eggs in the warm wood – and of course snakes like the rattlers and pythons that sense the infra-red radiation through special pits on their head. And why can’t they actually see the heat source? Now, I know you may not be a physicist but let me try to explain why this is impossible. Heard of the electromagnetic spectrum? Well, that’s a start. Now then visible light ranges from the ultraviolet (UV) towards the infrared, which we sense as warmth. UV has a shorter wavelength and packs more energy. That is why it is so dangerous, skin-cancers and other horrors. For vision to work the process of excitation in the retina needs a certain energy to trigger a signal and infrared radiation simply doesn’t pack the necessary punch. Infrared is invisible, OK?

Yes, of course

A python (top) and rattlesnake. Black arrows point to nostrils, red arrows point to the pit organs which allow them to “see” specific wavelengths of radiant heat (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Let’s take a closer look at those infrared detectors in the rattlesnake Crotalus and their relatives (collectively the crotalids). They are a nifty piece of biological engineering, consisting of a deep pit divided by a very thin membrane with a tiny opening but otherwise serves to define an inner and outer chamber. This membrane is rich in blood vessels, packed with mitochondria and the nerve cells that actually detect the incoming infrared radiation. These pits are fantastically sensitive, easily capable of working at the level of thousandths of a microwatt.

It turns out that this pit is much more like an eye, specifically the so-called pinhole camera-eye, than you might expect. Pinhole eyes have no lens, and the apertural size of the opening to the pit means it has a poor focus, but the comparison still holds. Not only is it exceedingly sensitive, but its ability to detect thermal contrasts means that it sees cool areas as “shadows”. But there is more. The nerves that inform the brain about the infrared radiation feed into the same areas as the real eyes. In fact the snake has four eyes, two camera-eyes and two pinhole eyes, and because they all overlap the snake enjoys stereoscopic vision.

It all depends on the question

“What is it like to have the mind of a bat?” asked the philosopher Thomas Nagel. At first sight “seeing” infrared or echoes (as do bats and whales), let alone electrical fields (like many fish) seems utterly alien. But is it? Remember your eyes really aren’t like cameras at all. Yes, they usually have a lens, can focus and control the apertural size (the pupil), but the images are constructed in the brain. Second, the melding of the infrared signals and optical signals in the brain of the rattlesnake is by no means unique and abundant evidence exists for the combining of different sensory pathways. So for an animal to “see” it requires some sort of nervous system, but the information doesn’t need to be transmitted by the optic nerve. So too to detect the signal you need a protein receptor, but it doesn’t need to be the canonical rhodopsin.

Animals possess an extraordinary range of sensory receptors, each designed to receive one or other of the incoming torrent of sensations. So they can be in the form of molecules to taste, pressure waves as sound, or electromagnetic waves in the form of infrared radiation. So too animals have neural equipment to make sense of these sensations, but lurking behind all this is the Big Question. This is the one that leads to a shuffling of feet and awkward clearing of throats, the question of qualia and consciousness. The redness of the sunset, the taste of garlic, the sadness of G minor. Are these just neurological fictions?

Text copyright © 2015 Simon Conway Morris. All rights reserved.

Further reading

Bakken, G.S. and Krochmal, A.R. (2007) The imaging properties and sensitivity of the facial pits of pitvipers as determined by optical and heat-transfer analysis. Journal of Experimental Biology 210, 2801-2810.

Ebert, J. and Westholt, G. (2006) Behavioural examination of the infrared sensitivity of rattlesnakes (Crotalus atrox). Journal of Comparative Physiology, A 192, 941-947.

Goris, R.C. (2011) Infrared organs of snakes: An integral part of vision. Journal of Herpetology 45, 2-14.

Gracheva, E.O. et al. (2010) Molecular basis of infrared detection by snakes. Nature 464, 1006-1011.

Van Dyke, J.U. and Grace, M.S. (2010) The role of thermal contrast in infrared-based defensive targeting by the copperhead, Agkistrodon contortrix. Animal Behaviour 79, 993-999.

Riddles in code; is there a gene for language?

‘I have…’

Words are like genes; on their own they are not very powerful. But apply them with others in the right phrase, at the right time and with the right emphasis, and they can change everything.

‘I have a dream…’

Genes are coded information. They are like the words of a language, and can be combined into a story which tells us who we are.

The stories we choose to tell are powerful; they can change who we become, and also change the people with whom we share them.

‘I have a dream today!’

Language is a means for coding and passing on information, but it is cultural, and definitely non-genetic. Nevertheless, for our speech capacity to have evolved, our ancestors must have had a body equipped to make speech sounds, along with the mental capacity to generate and process this language ‘behaviour’. Our body’s development is orchestrated through the actions of relevant genes. If the physical aspects of language ultimately have a genetic basis, this implies that speech must derive, at least in part, from the actions of our genes.

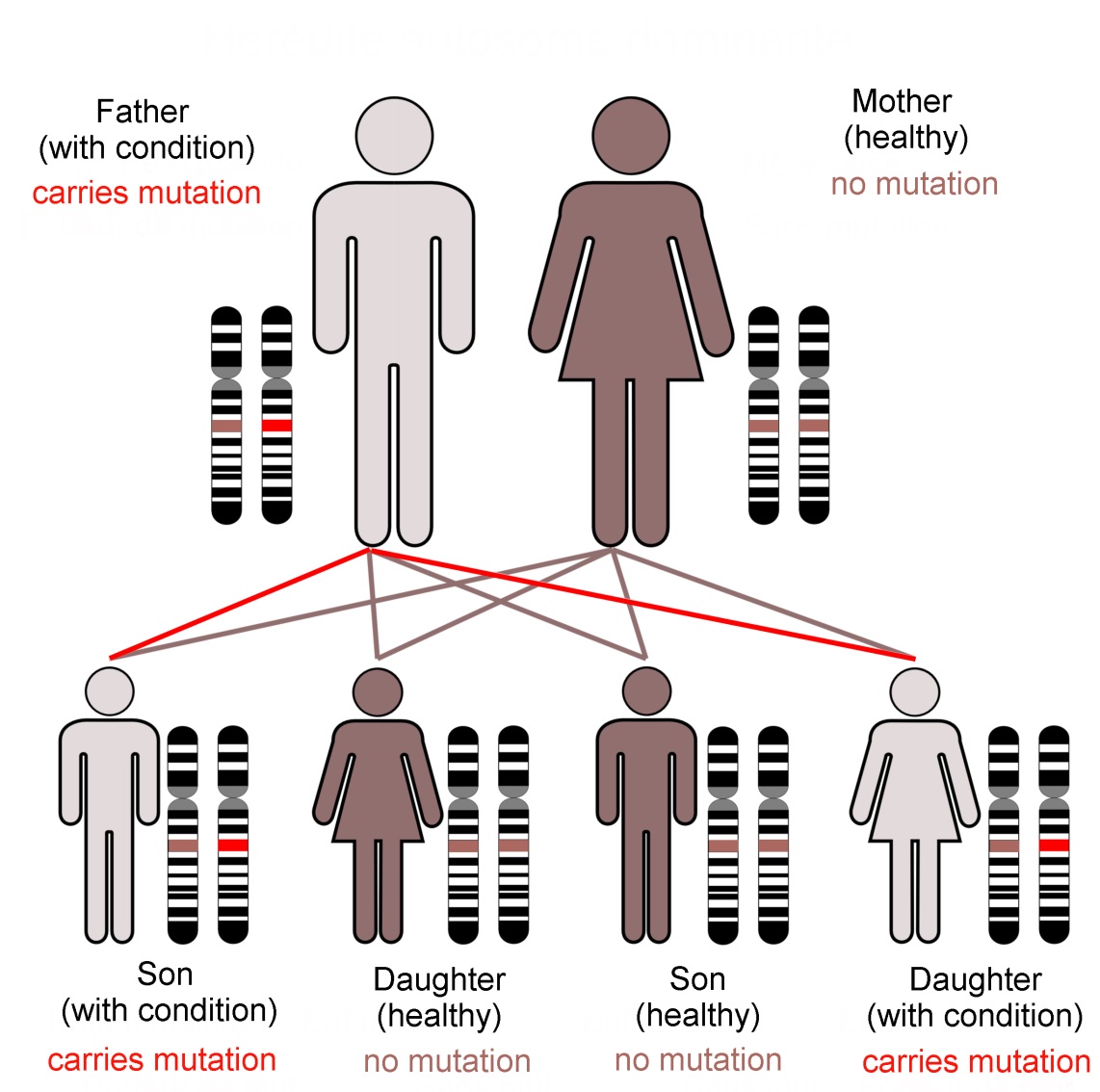

The hunt for genes involved with language led researchers at the University of Oxford to investigate an extended family (known as family KE). Some family members had problems with their speech. The pattern of their symptoms suggested that they inherited these difficulties as a ‘dominant’ character, and through a single gene locus.

The FOXP2 gene encodes for the ‘Forkhead-Box Protein-2’; a transcription factor. This is a type of protein that interacts with DNA (shown here as a pair of brown spiral ladders), and influences which genes are turne... mored on in the cell, and which remain silent. This diagram shows two Forkhead box proteins, which associate with each other when active. This bends the DNA strand and makes critical areas of the genetic code more accessible (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Discovery of another unrelated patient with the same symptoms confirmed that the condition was linked to a gene known as FOXP2 (short for ‘Forkhead Box Protein-2’). This locus encodes a ‘transcription factor’; a protein that influences the activation of many other genes. FOXP2 was subsequently dubbed ‘the gene for language’. Is that correct?

Not really. FOXP2 affects a range of processes, not just speech. The mutation which inactivates the gene causes difficulties in controlling muscles of the face and tongue, problems with compiling words into sentences, and a reduced understanding of language. Neuroimaging studies showed that these patients have reduced nerve activity in the basal ganglia region of the brain. Their symptoms are similar to some of the problems seen in patients with debilitating diseases such as Parkinson’s and Broca’s Aphasia; these conditions also show impairment of the basal ganglia.

Genes code for proteins by using a 3-letter alphabet of adenine, thymine, guanine and cytosine (abbreviated to A, T, G and C). These nucletodes are knwn as ‘bases’ (are alkaline in solution) and make matched pairs w... morehich form the ‘rungs of the ladder’ of the DNA helix. Substituting one base for another (as happens in many mutations) can change the amino acid sequence of the protein a gene encodes. Changes may make no impact on survival, allowing the DNA sequence to alter over time. Changes that affect critical sections of the protein (e.g. an enzyme’s active site), or critical proteins like FOXP2, are rare (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Genes provide the code to build proteins. Proteins are assembled from this coding template (the famous triplets) as a sequence of amino acids, strung together initially like the carriages of a train and then folded into their finished form. The amino acid sequences of the FOXP2 protein show very few differences across all vertebrate groups. This strong conservation of sequence suggests that this protein fulfils critical roles for these organisms. In mice, chimpanzees and birds, FOXP2 has been shown to be required for the healthy development of the brain and lungs. Reduced levels of the protein affect motor skills learning in mice and vocal imitation in song birds.

The human and chimpanzee forms of FOXP2 protein differ by only two amino acids. We also share one of these changes with bats. Not only that, but there is only one amino acid difference between FOXP2 from chimpanzees and mice. These differences might look trivial but they are probably significant. FOXP2 has evolved faster in bats than any other mammal, hinting at a possible role for this protein in echolocation.

Mouse brain slice, showing neurons from the somatosensory cortex (20X magnification) producing green fluorescent protein (GFP). Projections (dendrites) extend upwards towards the pial surface from the teardrop-shaped ce... morell bodies. Humanised Foxp2 in mice causes longer dendrites to form on specific brain nerve cells, lengthens the recovery time needed by some neurons after firing, and increases the readiness of these neurons to make new connections with other nerves (synaptic plasticity). The degree of synaptic plasticity indicates how efficiently neurons code and process information (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Changing the form of mouse FOXP2 to include these two human-associated amino acids alters the pitch of these animals’ ultrasonic calls, and affects their degree of inquisitive behaviour. Differences also appear in their neural anatomy. Altering the number of working copies (the genetic ‘dose’) of FOXP2 in mice and birds affects the development of their basal ganglia.

Mice with ‘humanised’ FOXP2 protein show changes in their cortico-basal ganglia circuits along with altered exploratory behaviour and reduced levels of dopamine (a neurotransmitter that affects our emotional responses). So too, human patients with damage to the basal ganglia show reduced levels of initiative and motivation for tasks.

This suggests that FOXP2 is part of a general mechanism that affects our thinking, particularly around our initiative and mental flexibility. These are critical components of human creativity, and are as it happens, essential for our speech.

Basal ganglia circuits process and organise signals from other parts of the brain into sequences. Speaking involves coordinating a complex sequence of muscle actions in the mouth and throat, and synchronising these with the out-breath. We use these same muscles and anatomical structures to breathe, chew and swallow; our ability to coordinate them affects our speech, although this is not their primary role.

Family KE’s condition, caused by a dominant mutation in the FOXP2 gene, follows an autosomal (not sex-linked) pattern of inheritance, as shown here.Dominant mutations are visible when only one gene copy is present. In... more contrast a recessive trait is not seen in the organism unless both chromosomes of the pair carry the mutant form of the gene. The FOXP2 transcription factor protein is required in precise amounts for normal function of the brain. The loss of one working FOXP2 gene copy reduces this ‘dose’ which is enough to cause the problems that emerged as family KE’s symptoms (Image: Annotated from Wikimedia Commons)

In practice, very few of our 25,000 genes are individually responsible for noticeable characteristics. Most genetically inherited diseases result from the effects of multiple gene loci. FOXP2 is unusual because of its ‘dominant’ genetic character. It does not give us our language abilities, but it is involved in the neural basis of our mental flexibility and agility at controlling the muscles of our mouths, throats and fingers.

In addition, genes are only part of the story of our development. The way we think and subsequently behave alters our emotional state. Feeling stressed or calm affects which circuits are active in our brain. This alters the biochemical state of body organs and tissues, particularly of the immune system, modifying which genes they are using.

The dance between the code stored in our genes and the consequences of our thoughts builds us into what we are mentally, physically and socially. This story is ours to tell. By our experience, and with this genetic vocabulary, we create what we become.

Text copyright © 2015 Mags Leighton. All rights reserved.

References

Chial H (2008) ‘Rare genetic disorders: Learning about genetic disease through gene mapping, SNPs, and microarray data’ Nature Education 1(1):192 http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/rare-genetic-disorders-learning-about-genetic-disease-979

Clovis YM et al. (2012) ‘Convergent repression of Foxp2 3′UTR by miR-9 and miR-132 in embryonic mouse neocortex: implications for radial migration of neurons’ Development 139, 3332-3342.

Enard, W (2011) ‘FOXP2 and the role of cortico-basal ganglia circuits in speech and language evolution’ Current Opinion in Neurobiology 21; 415–424

Enard, W et al (2009) A Humanized Version of Foxp2 Affects Cortico-Basal Ganglia Circuits in Mice Cell 137 (5); 961–971 http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S009286740900378X

Feuk L et at., Absence of a Paternally Inherited FOXP2 Gene in Developmental Verbal Dyspraxia, in The American Journal of Human Genetics, Vol. 79 November 2006, p.965-72.

Fisher SE and Scharff C (2009) ‘FOXP2 as a molecular window into speech and language’ Trends in Genetics 25 (4); 166-177

Lieberman P (2009) ‘FOXP2 and Human Cognition’ Cell 137; 800-803

Marcus GF & Fisher SE (2003) ‘FOXp2 in focus; what can genes tell us about speech and language?’ Trends in Cognitive Sciences 7(6); 257-262

Reimers-Kipping S et al. (2011) ‘Humanised Foxp2 specifically affects cortico-basal ganglia circuits’ Neuroscience 175; 75-84

Scharff C & Haesler S (2005) ‘An evolutionary perspective on Foxp2; strictly for the birds?’ Current opinion in Neurobiology 15:694-703

Vargha-Khadem F et al. (2005) ‘FOXP2 and the neuroanatomy of speech and language’ Nature Reviews Neuroscience 6, 131-138 http://www.nature.com/nrn/journal/v6/n2/full/nrn1605.html

Wapshott N (2013) ‘Martin Luther King's 'I Have A Dream' Speech Changed The World’ Huffington post, 28th August 2013 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/08/28/i-have-a-dream-speech-world_n_3830409.html

Webb DM & Zhang J (2005) ‘Foxp2 in song learning birds and vocal learning mammals’ Journal of Heredity 96(3);212-216

Bats; hunters that see in sound

You are out in the dark, alone. You become aware of a distant rhythmical clicking noise. Sensing danger, you change direction and head for cover. Seconds later you are punched by wave after wave of sound that hits your body like a machine gun. The noise bears down on you, loud as an aircraft, faster and faster, blurring into a roar….

…You are a moth, taken by an echolocating bat.

Bats aren’t blind. Their eyes work, but they live in a different world, requiring an extra sense. Using high frequency sounds, also known as ‘biosonar’ or ‘echolocation’, they can see in the dark. We see, hear touch, smell and taste by picking up cues in our environment. Biosonar is completely different; there can be no signal without the call.

A bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) with locator beacon; Persian gulf. This animal is part of a trained team of animals used by the US Navy for mine clearance in shipping lanes. Since most prey cannot detect high ... morefrequency sound, hunters using echolocation have a stealth surveillance system of near-military precision. Dolphin echolocation inspired naval underwater surveillance using sonar (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

This really is seeing in sound. Biosonar provides bats and some other animals, including dolphins, with a distinctive and sophisticated form of vision, giving detailed three-dimensional information over long distances in darkness or murky waters.

Bats illuminate their world with beams of directional sound

Most bats hunt using a range of frequencies, moving their heads to pulse sounds in different directions as they fly. Lower frequencies produce wider sound cones like a floodlight, and higher frequencies focus the beam like a spotlight.

Bats and other echolocators emit pulses of directional sound that echo back from a target, returning them a cone of sonic information. They control the length and width of this cone by altering the frequency of their ca... morells and how far they open their mouths when producing the pulse. Larger mouths and higher frequencies produce longer, narrower ‘visual’ sound cones (Image: ©Simon Crowhurst)

Although one lives in the forest and the other in the ocean, the way bats and dolphins use biosonar when hunting is almost identical. Dolphins, like bats, both shift the frequency of their clicks as they scan and lock onto prey, giving a characteristic ‘buzz’ of rapid calls as they take the target. Sound travels more quickly under water, so dolphin sonar operates over a longer range.

Bats project sound and receive echoes the way that eyes scan an image

Watch someone’s eyes as they examine something; their gaze jerks from one area to another. These are known as ‘saccade and fixate’ movements. They focus different parts of the image onto an area at the back of the eye called the fovea, which sees detail. ‘Saccade and fixate’ eye patterns are found in all animals with good vision, and is a defining characteristic for how eyes focus on details.

The human eye shifts its main focus in a series of ‘saccade and fixate’ movements. As this eye focusses on Sophocles’ hand, reflected light from the object lands on the fovea; the detail-harvesting area at the bac... morek of the eye. When looking at an object, our eyes move suddenly from one detail to another (the saccade), and then ‘fixate’ for a few moments onto these points of interest.Sophocles uses the idea of blindness in his story, ‘Oedipus Rex’, to illustrate how seeing is a highly active process, whether this is physical or metaphorical (Image: Composite of images from Wikimedia Commons)

When our eyes focus, they project an image onto an area at the back of our eyes known as the ‘fovea’. This zone is specialised to pick up high levels of detail. Any sense can be developed to pick up a high level of detail; we use sight, bats use sound, and star-nosed moles use touch.

Most bats hunt insects in the open air, listening for the returning echoes before making their next signal. They use a combination of head movements and focussed sound cones to gain information in a classic ‘saccade and fixate’ pattern. Wider head scanning and lower frequency calls provide a ‘wide angle’ view with less detail. Higher frequency calls and a narrow range of head movements create an ‘acoustic fovea’; this focuses their sonic gaze onto a small area and recovers detail, much like ‘zooming in’ using a macro lens.

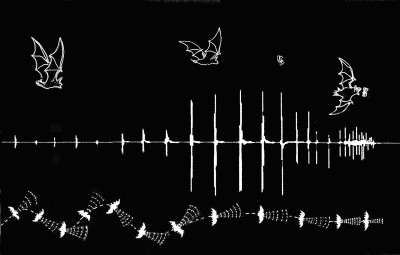

This artist’s impression shows the flight path (below) and behaviour (above) during the hunting sequence of a Common Pipistrelle bat (Pipistrellus pipistrellus), represented by the sound trace (centre). The process ha... mores distinct phases. During the initial ‘search’ (left), the call frequency is quieter (lower amplitude) and less frequent; this produces a wide angle sound cone. Upon detecting and approaching a target (centre), the hunter’s calls increase in volume and frequency, which focusses the acoustic gaze. As the hunter is locked onto its target (right), it produces a high frequency ‘buzz’. This highly focussed cone of sound allows the bat to perceive details, and manoeuvre very precisely as it closes in to take the prey.The time from detecting to taking the prey is less than a second. (Image: ©Simon Crowhurst)

Horseshoe bats use echolocation in a different way; an adaptation to hunting in and around the spatially variable (and hence acoustically complicated) ‘surface’ of tree and shrub canopies. They use mostly constant-frequency pulses, and listen for Doppler-shifted returning echoes. The cochlear membranes of their inner ears respond over a broad frequency range, but have particular sensitivity within a very narrow bandwidth (their acoustic fovea). When locking the sound pulse onto their prey, they alter their emitted call in order to keep the frequency of the returning echoes constant. This allows them to focus on the frequency modulations caused by the fluttering movements of large insects.

Echolocation reveals shape and form using ‘stereo’ images

Just as the brain uses the different view from our two eyes to build a stereo image, our brains use the differences between what is heard by our ears to understand something of the direction and distance of a sound source. Bats use this difference to understand and construct a ‘stereo image’ of their surroundings in three dimensions. This enables them to understand something of the shapes and textures of objects in their environment.

Some tropical bats are nectar feeders. Flowers hidden amongst the leaves are in an acoustically cluttered environment. Many flowering plants using bats to assist with their pollination have evolved floral structures that act as ‘sound beacons’. These are usually dish-shaped (parabolic) and bounce back an unique echo pattern that makes them become acoustically visible.

The Allen Telescope Array (ATA) built by the University of California, Berkeley and SETI (Search for Extra-terrestrial Intelligence). This offset Gregorian design reflects incoming radio waves caught by the large parabo... morelic dish onto the secondary parabolic reflector, which harvests the signal. The telescope is tuned to a frequency range from 0.5 to 11.2 GHz and will eventually have 350 antennae (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Parabolic shapes also make excellent receivers. The Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI) project’s radio telescope is made of many parabolic ‘ears’, listening for radio transmissions from outer space. Whilst we have invented technologies enabling us to hear bat calls and signals from beyond our planet, our own ears’ convoluted parabolic shape also captures sounds, and funnels them to our receiver; the ‘ear drum’ .

Text copyright © 2015 Mags Leighton. All rights reserved.

References

Fenton, M.B. (2013) Questions, ideas and tools; lessons from bat echolocation. Animal Behaviour 85, 869-879.

Connor, W.E. and Corcoran, A. J. (2012) Sound strategies; the 65 million year old battle between bats and insects. Annual Review of Entomology 57, 21-39.

Ghose, K. et al. (2006) Echolocating bats use a nearly time-optimal strategy to intercept prey. PLoS Biology 4, 865-873.

Jakobsen, L. et al. (2013) Convergent acoustic field of view in echolocating bats. Nature 493, 93-96.

Land, M.F. (2011) Oculomotor behaviour in vertebrates and invertebrates In The Oxford Handbook of Eye Movements(S.P.Liversedge, I.D. Gilchrist and S. Everling, eds), pp. 3-15. Oxford University Press.

Ratcliffe J A et al. (2012) ‘How the bat got its buzz’ Biology Letters 9;20121031

Siebert, A M et al (2013) ‘Scanning behaviour in echolocating common pipistrelle bats (Pilistrellus pipistrellus) Plos One 8(4);e60752

Simon et al (2011) ‘Floral acoustics; conspicuous echoes of a disc-caped leaf attract bat pollinators’ Science 333: pp631-633

Schnitzler, H-U. and Denzinger, A. (2011) Auditory fovea and doppler shift compensation: adaptations for flutter detection in echolocating bats using CF-FM signals. Journal of Comparative Physiology, A 197, 541-559.

Surlykke, A. et al. (2009) Echolocating bats emit a highly directional sonar sound beam in the field. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, B 276, 853-860.

von Helversen, D. and von Helversen, O. (2003) Object recognition by echolocation; a nectar feeding bat exploiting the flowers of a rainforest vine. Journal of Comparative Physiology, A 189, 327-336.

von Helversen, D. and von Helversen, O. (1999) Acoustic guide in bat pollinated flower. Nature 398, 759-760.