Gut feelings; are microbes in your intestines dictating your mood?

A cat hears a scuffling sound amongst the garbage. She stands in shadow, all senses poised.

A few moments pass; the rat emerges. In this alleyway, a light breeze carries her scent towards him. He sniffs the air, and looks in her direction. Two eyes blink, and then fixate upon him.

But he does not heed the warnings. A parasite in his brain, picked up from cat faeces, has immobilised his fear response. He scuttles out across the floor…

We are mostly bacteria. The microbes living on our skin, on the inner surfaces of our lung linings and through our gut outnumber our body cells ten to one. In fact, bacteria and other micro-organisms live in and around all multicellular life forms – from plants to people. This ‘microbiome’ is

an essential part of our biology and our health, and even influences how we (and all other animals) behave.

Microbes begin to colonise our gut from the moment of our birth. They help to pre-digest our food, making nutrients soluble and hence available for absorption through the gut wall. But the helpfulness of these bacteria doesn’t stop here.

The many small fatty acids and amino acids produced by bacterial fermentation act as signals inside our bodies. They initiate the development of the network of nerves in the gut wall; our ‘enteric nervous system’ (also known as our ‘second brain’). These nerves control the rhythmical contractions of the digestive canal, which operate independently of the central nervous system. Bacterial products also initiate, nourish and maintain the cells lining our gut.

A thin section of the small intestine wall, stained for CK20 protein (found in the mucosal lining).The lining of our intestines is a vast sensory surface, whose cells are nourished by fatty acids, vitamins and other com... morepounds produced by bacterial fermentation. The finger-like projections (called villi) visible in this section, form our main absorptive surface for nutrients, and sense the presence of both friendly bacteria and harmful pathogens (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

However the role of this microbial community goes beyond digestion.

– They out-compete harmful bacteria, ‘policing’ the gut and maintaining its pH.

– They present antigen signals (bacterial surface proteins) to our immune system, training us to recognise ‘friend’ from ‘foe’.

– They produce neurotransmitters and hormones, which are used directly and indirectly by the body. These include the cytokines and chemokines needed by immune cells to induce inflammation and fever responses and to target white blood cells into infected tissues. Bacteria produce precursors for 95% of our body’s serotonin (the ‘feel good’ brain chemical), and 50% of our dopamine.

Bacterial products affect the formation of connections between neurons (the synapses).

The enteric nervous system interacts with the central nervous system via the vagus nerve (the parasympathetic system) and the prevertebral ganglia (sympathetic nervous system). However if these nerve connections are sev... moreered, the enteric system will continue to function, integrating and resolving signals from the body and the environment. This network uses around 30 neurotransmitters, most of which are also found in the brain, and which include acetylcholine, dopamine and serotonin (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Our ‘gut-brain axis’ is linked indirectly by chemicals the bacteria produce, which activate the immune system. Our mind and gut is also linked directly via the vagus nerve.

The vagus or ‘wandering’ nerve, our 10th cranial nerve, forms part of the parasympathetic (involuntary) nervous system. It is a ‘mixed nerve’, meaning it carries both sensory information about our body state back to the brain, including from the gut to the brain stem, and relaying messages from the brainstem and emotional centres to the body.

This information highway operates the ‘vagal reflex’, which relaxes the muscles around the stomach wall making space for our food, and also integrates the digestive process with our blood circulation, hormone system and emotional state.

This conversation between the digestive, immune, hormonal and nervous systems is essential for our healthy development. Mice raised under sterile conditions (so that their guts are free of bacteria) develop fewer connections between neurons, which results in retarded brain growth.

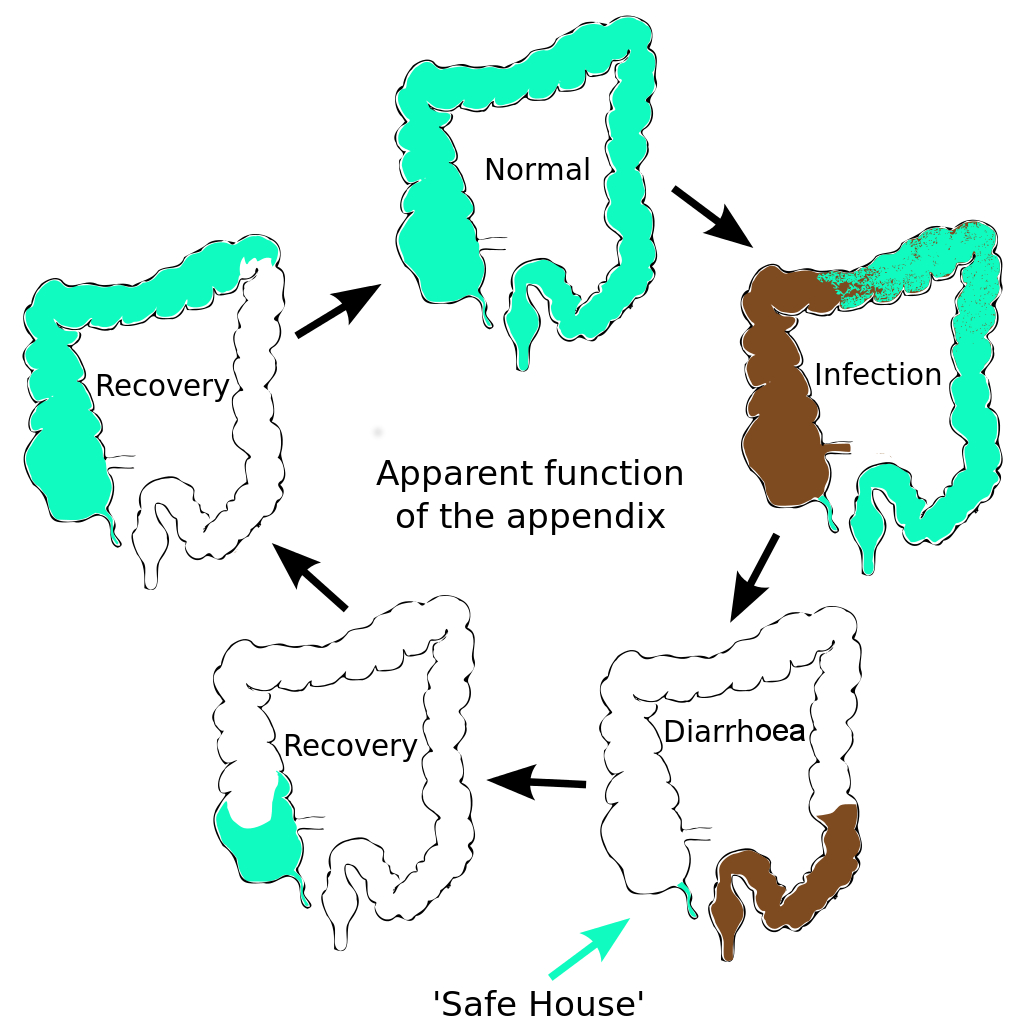

The human appendix is surrounded by copious amounts of immune tissue which particularly nurture and protect this sub-sample of our gut bacterial community. This creates a ‘safe house’ for a sample of our gut microfl... moreora. After an infection has triggered a diarrhoea response which expels the intestinal contents, the guts are recolonized by bacteria from this reservoir in the appendix. Charles Darwin first suggested that the human appendix is a relic of our evolution; a ‘vestige’ of a much larger mammalian caecum. (A caecum is a larger area of gut, containing bacteria, adapted in herbivores to digest large amounts of plant material). However this explanation doesn’t fit the facts. The appendix has evolved at least twice, arising independently in marsupials and placental mammals; an example of evolutionary convergence. This suggests that it has a current and selectable function (Image: Amended from Wikimedia Commons)

Gut microbes also influence our mood and emotions, affecting our behaviour. If intestinal bacteria from timid mice are used to populate the guts of a normally inquisitive mouse strain, these more adventurous mice become timid. Likewise, timid mice become adventurous when given the microflora from inquisitive mice.

Behavioural effects are also visible in humans. One of the first studies, conducted in France by Michaël Messaoudi and co-workers, found that drinking milk fermented with probiotic bacteria (versus non-fermented milk) lifted the mood of healthy human volunteers, reduced their blood cortisol levels (a hormone which increases during stress) and gave them a greater resilience against stimuli provoking symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Just as gut bacteria influence our health and mood, experiences that change our mood and behaviour in turn affect the composition of this microbial community. This shows that our gut microbiota are not autonomous, but act like a fully integrated body organ. This microbiotic organ monitors and responds to the food we eat, influences how we respond to our world, and connects with our body using messages sent in a common chemical ‘language’ . We speak about our ‘gut feelings’, usually unaware that this is much more than a metaphor.

It seems then, that our thoughts, feelings and behavioural choices affect our gut microbiome. As we ‘tell them’ how we feel (through the parasympathetic nervous system, immune system and hormones), they align their metabolic responses with this information. Their biochemical cues reinforce the body’s signal by releasing neurologically active chemicals that affect our mood. If our enteric nervous system really does deserve its title of the ‘second brain’, then the bacteria in our gut are mediating a connection that integrates the ‘thoughts of our guts’ with those of our mind.

Lab mouse, strain mg 3204. Laboratory mice are usually derived from the house mouse (Mus musculus). Mice are useful as a system to study many aspects of human health, thanks to having a high similarity with our genetic ... morecode, as well as the ability to thrive in a human-influenced environment. As with humans, many aspects of their development and behaviour are dependent upon a healthy community of gut microflora (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Since we and all other animals are intimately associated with our gut bacterial ‘organ’, this raises interesting questions at the cellular level about where our physical boundaries really are.

Text copyright © 2015 Mags Leighton. All rights reserved.

References

Collins, S.M. and Bercik, P. (2013) Intestinal bacteria influence brain activity in healthy humans. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Herpetology 10, 326-327.

Cryan, J.F. and Dinan, T.G. (2012) Mind-altering micro-organisms; the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 13, 701-712.

David, L.A. et al. (2014) Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the gut microbiome. Nature 505, 559-566.

Diamond, B. et al. (2011) It takes guts to grow a brain. Bioessays 33, 588-591.

Faith, J.J. et al. (2011) Predicting a human gut microbiota's response to diet in gnotobiotic mice. Science 333, 101-104.

Forsythe, P. et al. (2010) Mood and gut feelings. Brain, Behaviour and Immunity 24, 9-16.

Frank, D.N. and Pace, N.R. (2008) Gastrointestinal microbiology enters the metagenomics era. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology 24, 4-10.

Heijtz, R.D. et al. (2011) Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behaviour. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 108, 3047–3052.

Jahan-Mihan, A. (2011) Dietary proteins as determinants of metabolic and physiologic functions of the gastrointestinal tract. Nutrients 3, 574-603.

Kurokawa. K. et al. (2007) Comparative metagenomics reveals commonly enriched gene sets in human gut microbiomes. DNA Research 14, 169-181.

Lee, W.J. and Brey, P.T. (2013) How microbes influence metazoan development: insights from history and Drosophila modelling of gut-microbe interactions. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 29, 571-592.

Lee, W.J. and Hase, K. (2014) Gut microbiota-generated metabolites in animal health and disease. Nature Chemical Biology 10, 416-424.

Lyer, L.M. et al. (2004) Evolution of cell-cell signalling in animals: did late horizontal gene transfer from bacteria have a role? Trends in Genetics 20, 292-299.

Messaoudi, M.et al. (2011) Assessment of psychotropic-like properties of a probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175) in rats and human subjects. British Journal of Nutrition 105,755-764.

Montiel-Castro, A.J. et al. (2013) The microbiota-gut-brain axis: neurobehavioural correlates, health and sociality. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 7, article 70.

O’Hara, A.M. and Shanahan, F. (2006) The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO Reports 7, 688-693.

Randal Bollinger, R. et al. (2007) Biofilms in the large bowel suggest an apparent function of the human vermiform appendix. Journal of Theoretical Biology 249, 826-831.