Coming up for air

Within a few hours of the naval sonar drill, reports arrived of stranded beaked whales appearing over many kilometres along the coast. These animals showed signs of decompression sickness, also known as ‘the bends’.

Post-mortems on these animals revealed gas and fat bubbles in their bones and tissues.

The deeper you dive, the more the pressure forces nitrogen and oxygen from your lungs to dissolve into your body tissues. If you then surface too quickly, these gases can come out of solution and form bubbles in your blood. These can block smaller blood capillaries, cutting off the oxygen supply to the affected tissues. Decompression sickness is a recurrent risk amongst scuba-divers who breathe compressed air, and breath-holding ‘free-divers’ who make too many consecutive dives.

We have a diving reflex like other mammals. As the water hits our face, our heart slows and muscles under the skin contract, shunting blood into the centre of our body. Water pressure increases by 1 Atmosphere for every... more 10m depth. At 2 Atmospheres, the air in our lungs is half its original volume. By 50 metres (5 Atmospheres), gaseous oxygen and nitrogen dissolves into our body tissues, and fluid floods into our lungs. The human free-diving depth record is 214 metres (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

In contrast, beaked whales routinely hunt for an hour below 1000m, using echolocation. These ‘extreme divers’ do not normally experience decompression sickness, although fossils from early in their evolutionary history show that they were not immune to these problems. X-rays of the fossilised bones of more primitive whales show regions where bubbles formed inside a capillary, damaging the bone tissue and leaving a tell-tale signature.

Whale embryos initially develop rear limb buds, like land mammals. These structures are reabsorbed back into the body later in development. The fossil record, along with DNA studies, reveal that whales’ closest living relatives are cows and hippos, which share their same four-legged (tetrapod), hoofed, land-dwelling ancestors.

The hind limbs of this Spotted Dolphin embryo (Stenella frontalis) are visible as small bumps (limb buds) near the base of the tail. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

This raises some puzzling questions:

– Why did whales’ ancestors take to the water after 300 million years on land?

– Why didn’t they re-evolve gills?

– How can they dive for so long without getting ‘the bends’?

Why did whales’ air breathing ancestors take to the water?

These North Ronaldsay sheep are descended from an Orkney population farmed here since Neolithic times. They graze along the shoreline, feeding almost exclusively on seaweed. Their rumen stomachs have an adapted bacteria... morel population which enables them to digest marine algae (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The land-dwelling ancestors of whales may have first waded into the sea to escape from predators on land. Shallow coastal areas offered a relatively safe haven with little competition for the new food resources available in or near the water. This initial stage would have enabled these semi-aquatic ancestors of modern whales to adapt their digestive systems to a marine food source.

Fossils from the early Eocene (52Ma) show a succession of increasingly aquatic forms. From crocodile-like and otter -like amphibious hunters, developmental changes remodelled their breathing, senses, kidney function and limbs to survive better in water. By 40Ma, these early whales had flippers, a fluked tail, and could mate, birth and suckle their young without leaving the water.

At the Eocene-Oligocene boundary (around 36Ma), movement of the continental plates opened up the deep waters of the circum-Antarctic ocean. This offered new ecological roles for the deeper-diving whales. Many new whale species appeared, including ancestors of the filter-feeding baleen whales and toothed whales that hunt in deep waters using echolocation.

Why didn’t whales re-evolve gills?

A sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) begins a dive; Gulf of Mexico. Adaptations for cold, deep waters include insulating blubber, lungs designed to collapse under pressure, and locomotion. The fluked tail is a super-e... morefficient ‘caudal oscillator’; both the up and down strokes generate lift, like a birds’ wing. These and other whale and seal species dive deep both to forage and to escape from killer whale (Orcinus orca) attacks (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The ability to breathe underwater like fish seems at first like a requirement for life in the sea. However despite their lack of gills, whales and dolphins are highly effective predators in both shallow and deep water.

Modern whales’ warm bodies enable their fast reflexes for hunting. Whilst swordfish and tuna have some warm muscles, most of their tissues are at sea water temperature. Were their whole bodies warm, the heat loss from their gills would be energetically too costly.

Fish gills develop from the ‘branchial arches’; bulging structures in the early vertebrate embryo. These same tissue bulges give rise to the lower jaw, the middle ear, hyoid bone and larynx in the throat of humans and other mammals. For whales and other mammals to form gills would require that they develop new embryonic structures; this would render redundant the lungs with their vast area of vascular tissue.

Breathing air enables whales to use vocal signals to coordinate their social groups and attract mates. Like land mammals, the baleen whales make vocal calls by passing a controlled air flow through the larynx. Echolocation, the alternative means of producing sound used by dolphins and other toothed whales, also requires air. Their ‘sonic lips’ generate calls in an air-filled nasal passage. Whilst many fish make sounds, their vocal abilities are simple and limited.

How do they dive for so long without getting ‘the bends’?

This diagram shows how myoglobin forms ‘alpha-helical’ spirals around a ‘haem’ co-factor. Haem’s ring-structure holds an iron atom, carrying an electrostatic charge. This attracts and holds an oxygen molecule ... more(red spheres). As carbon dioxide builds up it dissolves to form carbonic acid. This change of pH, alters the electrostatic balance, prompting myoglobin to release its oxygen. The myoglobin protein’s high positive charge also steadies the pH when cells break down sugars without oxygen and produce lactic acid (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

All mammals store oxygen in their muscles using a protein called myoglobin. Sustained activity during long foraging dives requires a lot of oxygen. Deep divers have much higher muscle myoglobin concentrations than land mammals, giving them substantial oxygen reserves.

Modern diving mammals, and deep diving fish such as tuna, have also modified their myoglobin. As early whales began to explore the deeper waters, selection resulted in better survival from individuals whose myoglobin carried a stronger positive electrostatic charge. Like positive magnetic poles, these ‘supercharged’ molecules repel each other. This keeps them in solution, allowing them to function at high tissue concentrations where most other proteins would clump together.

A supercharged form and high concentration of myoglobin makes it possible for deep diving mammals to return to the surface slowly after a prolonged dive. This behaviour avoids decompression sickness.

However when beaked whales and other species encounter naval sonar at depth, this causes them to ‘panic’ and surface too quickly, inducing ‘the bends’.

Text copyright © 2015 Mags Leighton. All rights reserved.

References

Balasse M et al. (2006) ‘Stable isotope evidence (δ13C, δ18O) for winter feeding on seaweed by Neolithic sheep of Scotland’ Journal of Zoology 270(1); 170-176

Beatty B L & Rothschild B M (2008) ‘Decompression syndrome and the evolution of deep diving physiology in the Cetacea’ Naturwissenchaft 95;793-801

Costa D P (2007) Diving physiology of marine vertebrates’ Encyclopedia of life sciences doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0004230

Ferguson S H et al. (2012) ‘Prey items and predation behavior of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Nunavut, Canada based on Inuit hunter interviews’ Aquatic Biosystems 8 (3); http://www.aquaticbiosystems.org/content/8/1/3

Gatesy J et al. (2013) ‘A phylogenetic blueprint for a modern whale’ Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution’ 66:479-506

Mirceta S et al. (2013) ‘Evolution of mammalian diving capacity traced by myoglobin net surface charge’ Science 340;1234192

Nery M F et al. (2013) ‘Accelerated evolutionary rate of the myoglobin gene in long-diving whales’ Journal of Molecular Evolution 76;380-387

Noren S R et al. (2012) ‘Changes in partial pressures of respiratory gases during submerged voluntary breath hold across odontocetes; is body mass important?’ Journal of Comparative Physiology B 182;299-309

Orpin C G et al. (1985) ‘The rumen microbiology of seaweed digestion in Orkney sheep’ Journal of Microbiology 58(6); 585-596

Rothschild B M et al (2012) ‘Adaptations for marine habitat and the effect of Jurassic and Triassic predator pressure on development of decompression syndrome in ichthyosaurs’ Naturwissenchaften 99;443-448

Steeman M E et al. (2009) ‘Radiation of extant cetaceans driven by restructuring the oceans’ systematic biology 58;573-585

Thewissen J G M et al (2007) ‘Whales originated from aquatic artiodactyls in the eocene epoch of India’ Nature 450;1190-1195

Thewissen J G M et al (2006) ‘Developmental basis for hind-limb loss in dolphins and origin of the cetacean body plan’ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 103(22); 8414–8418

Thewissen J G M and Sunil B (2001) ‘Whale origins as a poster child for macroevolution’ Bioscience 51(12);1037-1049

Tyack P L (2006) ‘Extreme diving of beaked whales’ Journal of Experimental Biology 209;4238-4253 Naturwissenchaften 99:443-448

Uhen M D (2010) ‘The origin(s) of whales’ Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 38;189-219

Uhen M D (2007) ‘Evolution of marine mammals; back to the sea after 300 million years’ The Anatomical Record 290;514-522

Williams T M (1999) ‘The evolution of cost efficient swimming in marine mammals; limits to energetic potimization’ Philosohical Transactions of the Royal Society of London series B 354;193-201

The reptile that almost became a fish

‘It’s head is as long as I am tall!’

‘What is it?’

‘Hmm… A giant fish? A lizard? Don’t know.’

‘Well I know! It’s a sea dragon!’

It is spring, 1811, the morning after a storm. Mary is 12 years old, and fearless. She edges across the cliff to where her brother is already working to free the fossil bones. Fragments of weathered mudstone clatter down onto the beach. The eye sockets of the huge skull are wider than the span of her hand.

A 185 million year old fossil of Ichthyosaurus acutirostris beside ammonites (Harpoceras falcifer). This specimen shows the distinctive downward (hypoocercal) bend of the spine into the lower tail fluke, characteristic ... moreof this reptile group. The outlines of the fluked tail and dorsal fin are visible; these were supported by cartilage rather than bone as in modern fish. The huge eye sockets (relative to its body size) enabled these animals to hunt by sight for shellfish, small fish and squid in dimly lit or murky waters (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

During the 200 million years that dinosaurs roamed the land, the oceans were ruled by formerly land-dwelling reptiles. Of these, ichthyosaurs adopted dolphin-like forms, plesiosaurs became sea lion-like, and mosasaurs occupied crocodile-like ‘ambush’ predator roles.

Of these, ichthyosaurs were arguably the most successful. Their multiple adaptations to a fully aquatic life included huge eyes, a stiffened, fluked tail, and the ability to mate and give birth to live young in water. Much as killer whales do today, these predators structured the marine ecosystem. Many came to resemble the modern whales, dolphins and tuna fish that now fulfil similar ecological roles. The convergence of body forms between some ichthyosaur species and tuna are particularly astonishing because these reptiles were air breathers.

Why did icthyosaurs evolve to look like modern marine animals?

Ichthyosaurs first colonised the sea 250Ma ago. The earliest known aquatic ichthyosaur, the otter-like Utatsusaurus hataii (top) fed on fish and shellfish in shallow water. After the Cretaceous-Tertiary mass extinction ... more(65Ma), the land-based ancestors of modern whales also took to water. The early whale Kutchicetus minimus (bottom) had an otter-like ecological role, and converged to evolve a similar body form. Both had an undulating swimming style which was in the horizontal plane (like an eel) for Utatsusarus, and vertical for Kutchicetus. This reflects the style of locomotion inherited from their respective ancestors (Images: Wikimedia Commons)

Life in water poses a specific set of challenges. These marine reptiles fulfilled similar ecological roles to whales, and in time evolved body forms similar to these modern mammals. This is known as convergence.

Like whales and tuna, ichthyosaurs were adapted for long distance energy-efficient swimming. The respective horizontal and vertical strokes of both ichthyosaur and dolphin tails give an equally powerful ‘lift’ in both directions, propelling these animals forward in a near straight line.

A further example of this convergence is seen in the modern otter. Unlike the Ichthyosaurs, both whales and otters had land-based mammalian ancestors with a vertically moving spine, giving them their bounding gait. The whale-like ichthyosaurs moved their tail flukes horizontally, like a modern lizard.

Like whales and tuna, ichthyosaurs were adapted for long distance energy-efficient swimming. The respective horizontal and vertical strokes of both ichthyosaur and , propelling these animals forward in a near straight line.

What can modern animals tell us about ichthyosaurs?

The ichthyosaur Stenopterygius quadriscissus (above), became widespread, in the late Jurassic and early Cretaceous (160-100Ma). Its body shape is similar to that of the Bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus (below). Tuna hunt f... moreish and squid at around 500m depth. This is possible because they have a high oxygen intake, fast metabolic rate, warm muscles, an energy efficient swimming style, and a higher heart rate and blood pressure than other fish (Images: Wikimedia Commons)

Modern tuna and lamnid sharks have converged into a similar ‘deep water sprint-predator’ ecological role. These long distance migrants move constantly at a moderate speed, except for short fast bursts when chasing prey. Chunky vertebrae stiffen their bodies at their core, reducing sideways movements except at the narrow ‘hinge’ before the tail. The continuously active red ‘cruising’ muscles either side of the spine are warm, in marked contrast to most other fish. In combination with large tendons, these muscles work like pulleys, flicking the fluked tail from side to side. The surrounding white muscles give extra power during short ‘sprints’.

The ichthyosaur Stenopterygius was tuna-shaped with chunky stacked vertebrae. This stiffened body form suggests that these reptiles converged on the cruise-and-sprint deep water hunting role of modern tuna and lamnids.

Did ichthyosaurs have warm muscles like whales and tuna?

Cast of a skeleton of Hawkins’ plesiosaur (Thalassiodracon hawkinsi) from the Lower Lias strata at Street in Somerset; part of England’s Jurassic coast. These rocks are rich in marine fossils of all kinds including ... morefish, ammonites and belemnites (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The isotopic proportion between the heavy 18O and the light 16O oxygen (the ratio is given as d18O) in the bones of living fish and marine animals decreases as body temperature increases. In principle we can use cold-blooded fish fossils as a ‘thermometer’ to indicate the water temperature, and compare this against isotope-predicted body temperatures for other fossil animals from the same rocks.

Oxygen isotope data allows us to infer that Jurassic plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs had body temperatures of around 35⁰C, much higher than that of their environment. This indicates that they could generate heat, and may well regulated their body temperatures independently of their environment (homeothermy). Modern warm bodied marine animals have to conserve their body heat. This means it is reasonable to infer that ichthyosaurs used similar methods such as a counter-current blood circulation system and/or heat-insulating blubber.

What happened to the ichthyosaurs?

Plotosaurus bennisoni; a mosasaur from the Upper Cretaceous of North America. Most mososaurs lived in shallow coastal waters, although after the disappearance of the ichthyosaurs, some evolved into similar deep water sp... morerint predators. Plotosaurus had crescent-shaped tail flukes, equipping this animal to whale-like fast pursuit behaviour (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Ichthyosaurs dominated the world’s oceans for around 150 million years, but then disappeared from the fossil record after the mid-Cretaceous (around 95Ma). The cause of their sudden extinction remains a mystery. The empty ecological roles that this created were later filled by mosasaurs; relatives of modern monitor lizards including the Komodo dragon. In turn these reptiles died out during the Cretaceous-Tertiary mass extinction (65Ma), making way for the later evolution of modern whales, dolphins and tuna.

Text copyright © 2015 Mags Leighton. All rights reserved.

References

Benson, R.B.J. and Butler, R.J. (2011) Uncovering the diversification history of marine tetrapods: ecology influences the effect of geological sampling biases In Comparing the Geological and Fossil Records: Implications for Biodiversity Studies ( A.J. McGowan and A.B.Smith, eds). Geological Society of London Special Publications 358, 191-208.

Bernal, D. et al. (2005) Mammal-like muscles power swimming in a cold-water shark. Nature 437: 1349-1352.

Brill, R.W. (1996) Selective advantages conferred by the high performance physiology of tunas, billfishes and dolphin fish. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, A 113, 3-15.

Brill, R.W. et al.(2005) Bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus) behavior and physiology and their relevance to stock assessments and fishery biology. Collective Volume of Scientific Papers ICCAT 57, 142-161. Online;http://www.iccat.es/en/pubs_CVSP.htm

Dickson, K.A. and Graham, J.B. (2004) Evolution and consequences of endothermy in fishes. Physiological and Biochemical Zoology 77, 998-1018.

Donley, J.M. (2004) Convergent evolution in mechanical design of lamnid sharks and tuna. Nature 429, 61-65.

Fröbisch, N.B. et al. (2013) Macropredatory ichthyosaur from the middle Triassic and the origin of modern trophic networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 110, 1393-1397.

Graham, J.B. and Dickson, K.A. (2004) Tuna comparative physiology. Journal of Experimental Biology 297, 4015-4024.

Houssaye, A. (2013) Bone histology of aquatic reptiles: what does it tell us about secondary adaptation to an aquatic life? Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 108, 3-21.

Korsmeyer, K.E. et al. (1996) The aerobic capacity of tunas; adaptation for multiple metabolic demands. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, A 113, 17-24.

Lindgren, J. et al. (2007) A fishy mosasaur: the axial skeleton of Plotosaurus (Reptilia, Squamata) reassessed. Lethaia 40,153–160.

Lindgren, J. et al. (2011) Landlubbers to leviathans: evolution of swimming in mosasaurine mosasaurs. Paleobiology 37, 445-469.

Lingham-Soliar, T. and Plodowski, G. (2007) Taphonomic evidence for high-speed adapted fins in thunniform ichthyosaurs. Naturwissenschaften 94, 65-70.

Malte, H. et al. (2007) Differential heating and cooling rates in bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus Lowe); a model of non-steady heat exchange. Journal of Experimental Biology 210, 2618-2626.

Motani, R. et al. (1998) Ichthyosaurian relationships illuminated by new primitive skeletons from Japan. Nature 393, 255-257.

Motani, R. (2002) Scaling effects in caudal fin propulsion and the speed of ichthyosaurs. Nature 415, 309-312.

Motani, R. (2002) Swimming speed estimation of extinct marine reptiles: energetic approach revisited. Palaeobiology 28, 251-262.

Motani, R. (2010) Warm-blooded “Sea Dragons”? Science 328, 1361-1362.

Rothschild, B. M. et al. (2012) Adaptations for marine habitat and the effect of Triassic and Jurassic predator pressure on development of decompression syndrome in ichthyosaurs. Naturwissenschaften 99, 443-448.

Syme, D.A. and Shadwick, R.E. (2011) Red muscle function in stiff bodied swimmers: there and almost back again. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, B 366, 1507-1515.

Thewissen, J.G.M. and Bajpai, S. (2009) New skeletal material of Andrewsiphius and Kutchicetus, two Eocene cetaceans from India. Journal of Paleontology 83, 635-663.

Elephants’ aquatic ancestors; just below the surface

Pausing on the bank, the lead female gathers her herd, ensuring that she is followed before she plunges in.

The smaller elephants swim, heads fully submerged. Others walk at first. All are snorkel-breathing through their trunks.

A lone male follows at a distance. He watches the tribe for a moment before he too enters the water.

Elephants are the largest land mammals, and are at home in hot, dry savannah environments. They migrate hundreds of miles in search of food, and when required will cross rivers, lakes, and even undertake marine excursions. They are surprisingly strong swimmers, and are the only mammals able to snorkel.

This provides a vital evolutionary clue to their past. Although we associate elephants with dry land, their bodies reveal clear evidence of an aquatic ancestry.

Fossils and DNA put elephants amongst the swimmers

DNA evidence:

Comparing DNA sequencesenables usto build molecular phylogenies, or ‘family trees’, defining the genetic relatedness between species. These phylogenies show that elephants’ closest living relatives are the fully aquatic sea cows; the dugongs and manatees.

Fossil evidence:

An artist’s impression of the semi-aquatic Moeritherium by scientific illustrator Heinrich Harder (1858-1935) (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Water molecules (H2O) contain three isotopes of oxygen; 16O, 17O and 18O. The lighter forms evaporate more easily, slightly enriching lakes and oceans with ‘heavy’ water. This then can become incorporated into aquatic plants and the bodies of animals that graze on them. Analysing the ratio of ‘light’ 16O to ‘heavy’ 18O isotopes (i.e. d18O) in teeth from fossils of the extinct elephant ancestor Moeritherium, show that they contain a higher proportion of 18O than teeth from land grazing animals. This tells us that it ate mostly freshwater plants, suggesting its lifestyle was at least semi-aquatic.

Elephant embryos reveal adaptations to breathing under water

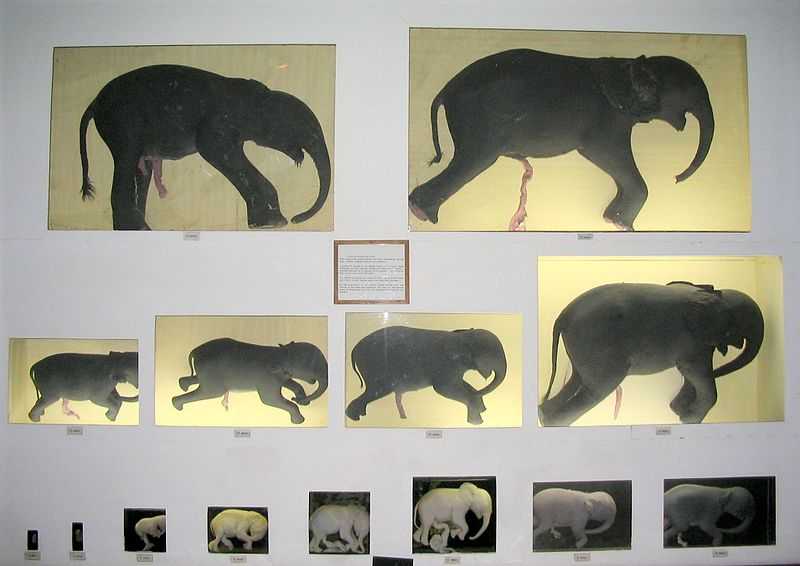

This photographic series of elephant foetuses shows the early appearance of the trunk. Natural History Museum, Maputo, Mozambique.An elephant foetus has detectable heart beats by day 80 of gestation, and the trunk start... mores to become visible at days 85-90. Overall, gestation is approximately 660 days (Image Wikimedia Commons)

Elephants can snorkel because of their elongated trunks, and elastic connective tissues that fill the space between their lungs and their body wall. Both of these features appear together early in the foetus, suggesting that they were important for survival of the elephant’s ancestors.

As in other large mammals, elephants’ blood pressure is high; this is needed to keep the brain well supplied with oxygenated blood. Under water, the differences between the pressure of inhaled air (atmospheric; 0mmHg) and the blood pressure in the capillaries (150mmHg) would be enough to rupture blood vessels and the delicate linings of the lung. Their elastic connective tissues act as shock absorbers, protecting the lungs against such damage.

Elephants’ testes are inside the body like other aquatic mammals

A male western grey kangaroo (Macropus fuliginosus) foraging near Port Douglas, Queensland. In hot weather, male kangaroos lower their scrotal sac away from the body; this helps keep these organs at a cooler temperature... more and avoids damaging their sperm (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The location of a mammal’s testes is related to temperature. Excessive heat or cold will kill mammal sperm (including humans), causing sterility. Hence in puberty, boys’ testes descend into sacs that are slightly cooler than the interior of their bodies. However aquatic mammals continue to carry their testes inside their abdomen to protect them from cold. We would expect land-dwelling elephants’ testes to be carried in a scrotum. Instead, their testes remain inside the body like those of aquatic mammals.

Early in the foetal development of both male elephants and dugongs, an artery develops which directly connects their kidneys and testes. In contrast, the testes of most land mammals have a less direct connection, allowing them to descend into a scrotum during puberty. This suggests that like modern dugongs, the elephants’ ancestors lack a scrotum.

Aquatic mammals including dugongs have a plexus of blood vessels that cool their internal testes and uterus through a counter-current heat exchange mechanism. Testicular cooling by a blood plexus has not yet been investigated in elephants; however in the absence of heat stress, they maintain a body temperature of around 34-36⁰C, which is similar to the temperature of the scrotum in most other land mammals.

Elephants ears close for swimming

This skull (formerly from a zoo elephant, kept at Basle in Switzerland) has had a front (sagittal) section removed, to show the honeycomb of air cavities inside the bones. Elephants hear low frequencies (infrasounds) tr... moreansmitted through the ground and conducted to their skull and inner ears through the bones of their front legs. These sounds are amplified by resonating in these inner bone chambers (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

After swimming we often have to shake our head to clear water from our ears. However elephant ears have a unique sphincter-like muscle that closes the ear canal and prevents water entry when swimming. This also creates a sealed ‘acoustic tube’, which works with the aerated bones and ‘acoustic fat’ lenses of the elephant skull to amplify low frequency ‘infrasound’. Dugongs have similar aerated skull bones and fatty deposits; again implying that they share an aquatic ancestor.

Text copyright © 2015 Mags Leighton. All rights reserved.

References

Fowler, M.E. and Mikota, S.K. (eds) (2006) Biology, Medicine, and Surgery of Elephants. Blackwell.

Gaeth, A.P. et al. (1999) The developing renal, reproductive and respiratory systems of the African elephant suggest an aquatic ancestry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 96, 5555-5558.

Hildebrandt, T. et al. (2007) Foetal age determination and development in elephants. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, B 274, 323-331.

Johnson, D.E. (1978) The origin of island mammoths and the Quaternary land bridge history of the Northern Channel Islands, California. Quaternary Research 10, 204-225.

Johnson, D.E. (1980) Problems in the land vertebrate zoogeography of certain islands and the swimming powers of elephants. Journal of Biogeography 7, 383-398.

Liu, A.G.S.C. et al. (2008) Stable isotope evidence for an amphibious phase in early proboscidean evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,USA 105, 5786-5791.

McKenchie, A.E. and Mzilikazi, N. (2011) Heterothermy in Afrotropical mammals and birds: a review. Integrative and Comparative Biology 51, 349-363.

O’Connell-Rodwell, C.E. (2007) Keeping an ear to the ground: seisemic communication in elephants. Physiology 22, 287-294.

Poulakakis, N. et al. (2006) Ancient DNA forces reconsideration of evolutionary history of Mediterranean pygmy elephantids. Biology Letters 2, 451-454.

Poulakakis, N. and Stamatakis, A. (2010) Recapitulating the evolution of Afrotheria: 57 genes and rare genomic changes consolidate their history. Systematics and Biodiversity 8, 395-408.

Seiffert, E.R. (2007) A new estimate of Afrotherian phylogeny based on simultaneous analysis of genomic, morphological and fossil evidence. BMC Evolutionary Biology 7, 224.

Springer, M.S. et al. (2004) Molecules consolidate the placental mammal tree. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 19, 430-438.

Weissenbrock, N.M. et al. (2012) Taking the heat: thermoregulation in Asian elephants under different climatic conditions. Journal of Comparative Physiology, B 182, 311-319.

West, J.B. Why doesn’t the elephant have a pleural space? Physiology 17, 47-50.

West, J.B. et al. (2003) Fetal lung development in the elephant reflects the adaptations required for snorkelling in adult life. Respiratory Physiology and Neurobiology 138, 325-333.

West, J.B. (2001) Snorkel breathing in the elephant explains the unique anatomy of its pleura. Respiration Physiology 126, 1-8.