Seeing red: for happy faces, or snakes in the grass?

باربرا مكلينتوك

Can humans interbreed with other species?

No, don’t be ridiculous

What a disgusting suggestion! Uck!! A criminal conviction for bestiality will earn you a thumping prison-sentence and an odium that will shrink your social life. Anycase, have you forgotten the text-book definition of a species? That’s right; key to the concept are that populations must be reproductively isolated. So no inter-specific hanky-panky, thank you very much. It is just as well animals don’t read the text-books because in reality species do interbreed (and you should see the plants …). Such hybridization occasionally opens new evolutionary doors, but more often the outcome of such miscegenation is sterility. And what about us, Homo sapiens? No question that we descended from other species, but now alone we proudly stand. Would we ever stoop to interbreeding? Perish the thought!

Yes, of course

Our genomes tell a very different story. We may be alone, but a little beyond historical memory we had close companions in the form of the Neanderthals and the more recently discovered Denisovans. Skeletons of the former abound and reveal a powerfully built customer. Given Denisovans are known from only a couple of teeth and a tiny finger bone, reconstructing their original appearance might seem a tall order. Let’s ask Holmes: “Observe, Watson, mere scraps, but the tooth, is it not somewhat archaic? Summon one of my Irregulars, I want this finger-bone to be taken poste-haste to that ingenious DNA lab in Leipzig …”. Ingenious indeed, because not withstanding almost invariably massive microbial contamination, original DNA is not only recovered but it confirms that although Denisovans, humans and Neanderthals are genomically near-identical there real differences in the DNA and they yield extraordinary insights. First, Denisovans and Neanderthals are the closer cousins (separating about 550,000 years ago), whilst we and Neanderthals went our separate ways perhaps a quarter of million years later. Did I say “separate”? Not quite. Lurking in our genomes are chunks of Denisovan and Neanderthal DNA and they didn’t get there by sneezing. The only explanation is interbreeding, in the trade this transfer is known as introgression. The story, however, is a bit more complicated. Writing as a Eurasian roughly 2% of my DNA is Neanderthal. Amongst Asians this figure is slightly higher, but if we look at sub-Saharan Africa then with the curious exception of the Maasai only a trace of this imported DNA can be found. So did they escape introgression? Not at all; sub-Saharan people carry a tell-tale signature of a separate encounter with another archaic hominin, and perhaps as recently as 35,000 years ago. The Denisovan story is if anything more intriguing. In the inhabitants of Papua New Guinea about 6% of the DNA is of Denisovan origin and appreciable amounts are also found in surrounding populations. Whilst these genomic footprints provide unequivocal evidence of interbreeding, successful hybridizations were still extremely rare. One estimate suggests one successful mating roughly every eighty generations will suffice to ensure the transfer of Neanderthal or Denisovan DNA.

It all depends on the question

So does this introgressed DNA make us any less human? Not at all! First of all humans readily interbreed. Whether or not you are the proud carrier of Neanderthal or Denisovan DNA makes no difference at all. We are one species. Note also that the original quantities of imported DNA were probably greater, but some of the visitor DNA has been shown to the door. It is no coincidence that in this respect the X-chromosome is notably “clean”; on this sex-chromosome introgressed DNA might do real damage. Elsewhere, however, there might be real advantages, although deciding exactly how is more tricky. First, by no means all living human populations have the same profiles of introgression so any benefits cannot be universal. Second, genomic history is complex; in some cases the DNA may actually derive from an older common ancestor. This is important because features such as language might significantly predate the emergence of Neanderthals, Denisovans and ourselves. Third, genes are usually multifunctional and it is risky to say gene A does only function X. Even so there are some interesting links. Most striking, perhaps, is the clear connection between the remarkable adaptability of Tibetans to high altitude-life and what is clearly a Denisovan import. To be sure other links are more tenuous, but they may include skin colour (and hence UV protection or vitamin D synthesis), skeletal structure, the immune system and cognitive capacities.

Details of when, where and how often these hominin species met are sketchy, but the introgressed DNA we carry is mute testimony to a far more complex history of distributions, contacts and migrations than was once imagined. And as the unexpected discovery of the “hobbits” on Flores (at conferences they are called Homo floresiensis) should remind us, maybe there were still other early hominins roving the planet at the same time, yet to be discovered? Remember that currently the Denisovans are known from only a single Siberian cave. To explain, however, where the remnants of their DNA are now found can only be explained if originally they had a huge geographical range, rivalling that of the Neanderthals. The Denisovans are yet to tell their full story, but in the case of the Neanderthals a persistent idea is that despite their success ultimately their extinctions were the result of coming second-best, runners-up against the smarter us. Maybe so, but evidence from diets, cooking, hunting, clothing, technology and most importantly cultural and symbolic activities suggest that it could have as easily been a Neanderthal writing these lines. Maybe their fatal flaw was tiny populations that were too vulnerable. Even so, Neanderthals possessed speech … and imagination. Forever gone, now they haunt our imaginations. It is an early summer day near the River Jordan and mist floats across the Palaeolithic meadow. Was it an accident or already arranged? Either way Neanderthal and human, male and female meet. Boy meets girl as they say, but this time across the species boundary. 50,000 years later we still carry a clear genetic memory of this fleeting meeting.

Text copyright © 2015 Simon Conway Morris. All rights reserved.

Further reading

Abi-Rached, L. et al. (2011) The shaping of modern immune systems by multiregional admixture with archaic humans. Science 334, 89-94.

Ding, Q-L. et al. (2014) Neanderthal introgression at chromosome 3p21.31 was under positive natural selection in east Asians. Molecular Biology and Evolution 31, 689-695.

Fu, Q-M. et al. (2015) An early modern human from Romania with a recent Neanderthal ancestor. Nature 524, 216-219.

Gokhman, D. et al. (2014) Reconstructing the DNA methylation maps of the Neanderthal and the Denisovan. Science 344, 523-527.

Hardy, B.L. et al. (2013) Impossible Neanderthals? Making string, throwing projectiles and catching small game during Marine Isotope Stage 4 (Abri du Maras, France). Quaternary Science Reviews 82, 23-40.

Hawks, J. (2013) Significance of Neandertal and Denisovan genomes in human evolution. Annual Review of Anthropology 42, 433-449.

Huerta-Sánchez, E. et al. (2014) Altitude adaptation in Tibetans caused by introgression of Denisovan-like DNA. Nature 512, 194-197.

Lachance, J. et al. (2012) Evolutionary history and adaptation from high-coverage whole-genome sequences of diverse hunter-gatherers. Cell 150, 457-469.

Mendez, F.L. et al. (2012) A haplotype at STAT2 introgressed from Neanderthals and serves as a candidate of positive selection in Papua New Guinea. American Journal of Human Genetics 91, 265-274.

Meyer, M. et al. (2012) A high-coverage genome sequence from an archaic Denisovan individual. Science 338, 222-226.

Neves, A.G.M. and Serva, M. (2012) Extremely rare interbreeding events can explain Neanderthal DNA in living humans. PLoS ONE 7, e47076.

Overmann, K.A. and Coolidge, F.L. (2013) Human species and mating systems: Neandertal-Homo sapiens reproductive isolation and the archaeological and fossil records. Journal of Anthropological Sciences 91, 91-110.

Prüfer, K. et al. (2014) The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains. Nature 505, 43-49.

Sankararaman, S. et al. (2012) The date of interbreeding between Neandertals and modern humans. PLoS Genetics 8, e1002947.

Sankararaman, S. et al. (2014) The genomic landscape of Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans. Nature 507, 354-357.

Wall, J.D. et al. (2013) Higher levels of Neanderthal ancestry in East Asians than in Europeans. Genetics 194, 199-209.

Riddles in code; is there a gene for language?

‘I have…’

Words are like genes; on their own they are not very powerful. But apply them with others in the right phrase, at the right time and with the right emphasis, and they can change everything.

‘I have a dream…’

Genes are coded information. They are like the words of a language, and can be combined into a story which tells us who we are.

The stories we choose to tell are powerful; they can change who we become, and also change the people with whom we share them.

‘I have a dream today!’

Language is a means for coding and passing on information, but it is cultural, and definitely non-genetic. Nevertheless, for our speech capacity to have evolved, our ancestors must have had a body equipped to make speech sounds, along with the mental capacity to generate and process this language ‘behaviour’. Our body’s development is orchestrated through the actions of relevant genes. If the physical aspects of language ultimately have a genetic basis, this implies that speech must derive, at least in part, from the actions of our genes.

The hunt for genes involved with language led researchers at the University of Oxford to investigate an extended family (known as family KE). Some family members had problems with their speech. The pattern of their symptoms suggested that they inherited these difficulties as a ‘dominant’ character, and through a single gene locus.

The FOXP2 gene encodes for the ‘Forkhead-Box Protein-2’; a transcription factor. This is a type of protein that interacts with DNA (shown here as a pair of brown spiral ladders), and influences which genes are turne... mored on in the cell, and which remain silent. This diagram shows two Forkhead box proteins, which associate with each other when active. This bends the DNA strand and makes critical areas of the genetic code more accessible (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Discovery of another unrelated patient with the same symptoms confirmed that the condition was linked to a gene known as FOXP2 (short for ‘Forkhead Box Protein-2’). This locus encodes a ‘transcription factor’; a protein that influences the activation of many other genes. FOXP2 was subsequently dubbed ‘the gene for language’. Is that correct?

Not really. FOXP2 affects a range of processes, not just speech. The mutation which inactivates the gene causes difficulties in controlling muscles of the face and tongue, problems with compiling words into sentences, and a reduced understanding of language. Neuroimaging studies showed that these patients have reduced nerve activity in the basal ganglia region of the brain. Their symptoms are similar to some of the problems seen in patients with debilitating diseases such as Parkinson’s and Broca’s Aphasia; these conditions also show impairment of the basal ganglia.

Genes code for proteins by using a 3-letter alphabet of adenine, thymine, guanine and cytosine (abbreviated to A, T, G and C). These nucletodes are knwn as ‘bases’ (are alkaline in solution) and make matched pairs w... morehich form the ‘rungs of the ladder’ of the DNA helix. Substituting one base for another (as happens in many mutations) can change the amino acid sequence of the protein a gene encodes. Changes may make no impact on survival, allowing the DNA sequence to alter over time. Changes that affect critical sections of the protein (e.g. an enzyme’s active site), or critical proteins like FOXP2, are rare (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Genes provide the code to build proteins. Proteins are assembled from this coding template (the famous triplets) as a sequence of amino acids, strung together initially like the carriages of a train and then folded into their finished form. The amino acid sequences of the FOXP2 protein show very few differences across all vertebrate groups. This strong conservation of sequence suggests that this protein fulfils critical roles for these organisms. In mice, chimpanzees and birds, FOXP2 has been shown to be required for the healthy development of the brain and lungs. Reduced levels of the protein affect motor skills learning in mice and vocal imitation in song birds.

The human and chimpanzee forms of FOXP2 protein differ by only two amino acids. We also share one of these changes with bats. Not only that, but there is only one amino acid difference between FOXP2 from chimpanzees and mice. These differences might look trivial but they are probably significant. FOXP2 has evolved faster in bats than any other mammal, hinting at a possible role for this protein in echolocation.

Mouse brain slice, showing neurons from the somatosensory cortex (20X magnification) producing green fluorescent protein (GFP). Projections (dendrites) extend upwards towards the pial surface from the teardrop-shaped ce... morell bodies. Humanised Foxp2 in mice causes longer dendrites to form on specific brain nerve cells, lengthens the recovery time needed by some neurons after firing, and increases the readiness of these neurons to make new connections with other nerves (synaptic plasticity). The degree of synaptic plasticity indicates how efficiently neurons code and process information (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Changing the form of mouse FOXP2 to include these two human-associated amino acids alters the pitch of these animals’ ultrasonic calls, and affects their degree of inquisitive behaviour. Differences also appear in their neural anatomy. Altering the number of working copies (the genetic ‘dose’) of FOXP2 in mice and birds affects the development of their basal ganglia.

Mice with ‘humanised’ FOXP2 protein show changes in their cortico-basal ganglia circuits along with altered exploratory behaviour and reduced levels of dopamine (a neurotransmitter that affects our emotional responses). So too, human patients with damage to the basal ganglia show reduced levels of initiative and motivation for tasks.

This suggests that FOXP2 is part of a general mechanism that affects our thinking, particularly around our initiative and mental flexibility. These are critical components of human creativity, and are as it happens, essential for our speech.

Basal ganglia circuits process and organise signals from other parts of the brain into sequences. Speaking involves coordinating a complex sequence of muscle actions in the mouth and throat, and synchronising these with the out-breath. We use these same muscles and anatomical structures to breathe, chew and swallow; our ability to coordinate them affects our speech, although this is not their primary role.

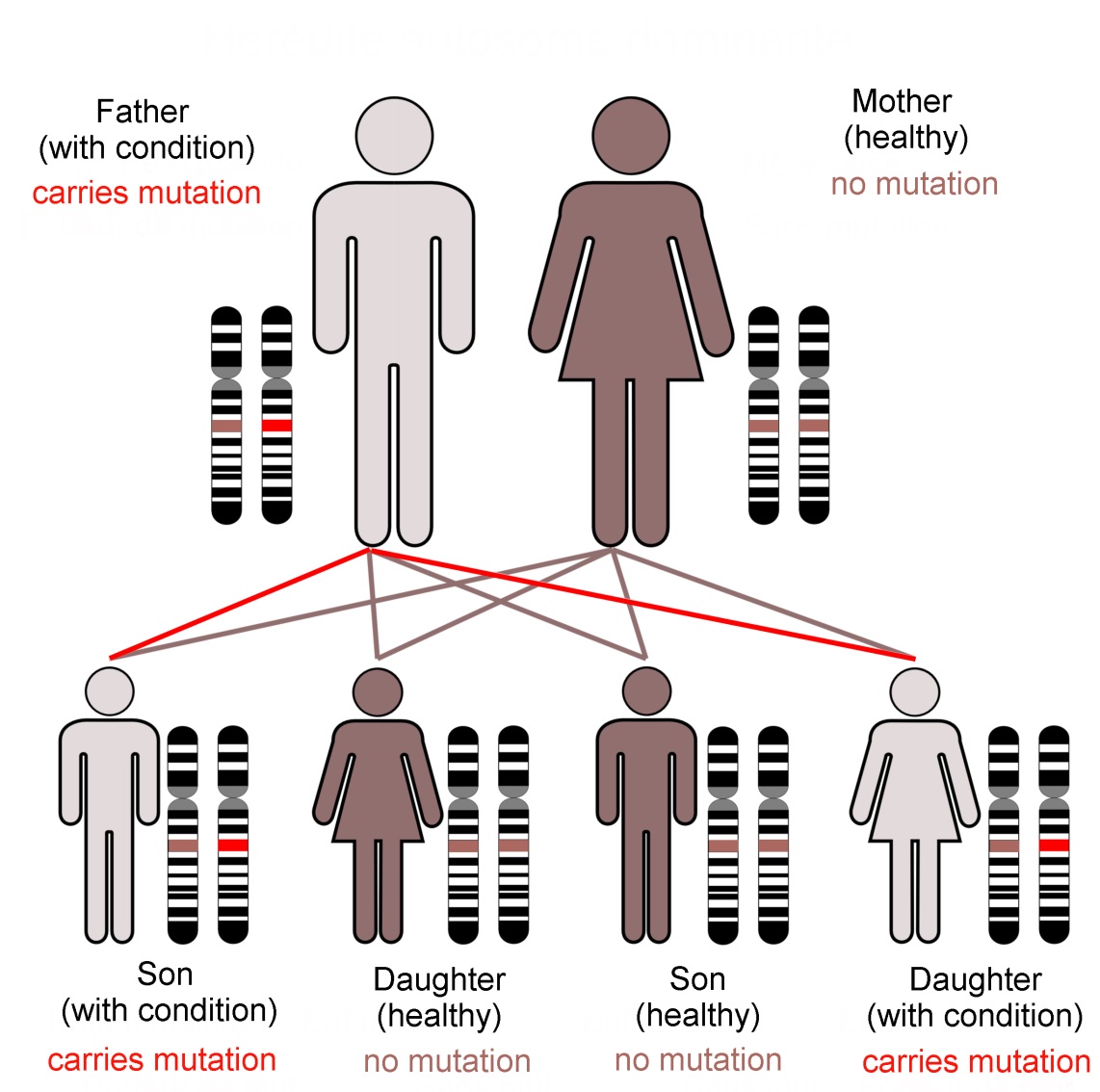

Family KE’s condition, caused by a dominant mutation in the FOXP2 gene, follows an autosomal (not sex-linked) pattern of inheritance, as shown here.Dominant mutations are visible when only one gene copy is present. In... more contrast a recessive trait is not seen in the organism unless both chromosomes of the pair carry the mutant form of the gene. The FOXP2 transcription factor protein is required in precise amounts for normal function of the brain. The loss of one working FOXP2 gene copy reduces this ‘dose’ which is enough to cause the problems that emerged as family KE’s symptoms (Image: Annotated from Wikimedia Commons)

In practice, very few of our 25,000 genes are individually responsible for noticeable characteristics. Most genetically inherited diseases result from the effects of multiple gene loci. FOXP2 is unusual because of its ‘dominant’ genetic character. It does not give us our language abilities, but it is involved in the neural basis of our mental flexibility and agility at controlling the muscles of our mouths, throats and fingers.

In addition, genes are only part of the story of our development. The way we think and subsequently behave alters our emotional state. Feeling stressed or calm affects which circuits are active in our brain. This alters the biochemical state of body organs and tissues, particularly of the immune system, modifying which genes they are using.

The dance between the code stored in our genes and the consequences of our thoughts builds us into what we are mentally, physically and socially. This story is ours to tell. By our experience, and with this genetic vocabulary, we create what we become.

Text copyright © 2015 Mags Leighton. All rights reserved.

References

Chial H (2008) ‘Rare genetic disorders: Learning about genetic disease through gene mapping, SNPs, and microarray data’ Nature Education 1(1):192 http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/rare-genetic-disorders-learning-about-genetic-disease-979

Clovis YM et al. (2012) ‘Convergent repression of Foxp2 3′UTR by miR-9 and miR-132 in embryonic mouse neocortex: implications for radial migration of neurons’ Development 139, 3332-3342.

Enard, W (2011) ‘FOXP2 and the role of cortico-basal ganglia circuits in speech and language evolution’ Current Opinion in Neurobiology 21; 415–424

Enard, W et al (2009) A Humanized Version of Foxp2 Affects Cortico-Basal Ganglia Circuits in Mice Cell 137 (5); 961–971 http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S009286740900378X

Feuk L et at., Absence of a Paternally Inherited FOXP2 Gene in Developmental Verbal Dyspraxia, in The American Journal of Human Genetics, Vol. 79 November 2006, p.965-72.

Fisher SE and Scharff C (2009) ‘FOXP2 as a molecular window into speech and language’ Trends in Genetics 25 (4); 166-177

Lieberman P (2009) ‘FOXP2 and Human Cognition’ Cell 137; 800-803

Marcus GF & Fisher SE (2003) ‘FOXp2 in focus; what can genes tell us about speech and language?’ Trends in Cognitive Sciences 7(6); 257-262

Reimers-Kipping S et al. (2011) ‘Humanised Foxp2 specifically affects cortico-basal ganglia circuits’ Neuroscience 175; 75-84

Scharff C & Haesler S (2005) ‘An evolutionary perspective on Foxp2; strictly for the birds?’ Current opinion in Neurobiology 15:694-703

Vargha-Khadem F et al. (2005) ‘FOXP2 and the neuroanatomy of speech and language’ Nature Reviews Neuroscience 6, 131-138 http://www.nature.com/nrn/journal/v6/n2/full/nrn1605.html

Wapshott N (2013) ‘Martin Luther King's 'I Have A Dream' Speech Changed The World’ Huffington post, 28th August 2013 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/08/28/i-have-a-dream-speech-world_n_3830409.html

Webb DM & Zhang J (2005) ‘Foxp2 in song learning birds and vocal learning mammals’ Journal of Heredity 96(3);212-216

Barbara McClintock

Barbara McClintock in her laboratory in 1947 (Image from the Smithsonian Institution collection via Wikimedia Commons)

Barbara McClintock (1902-1992) was an American geneticist and a pioneer in the field of cytogenetics, a branch of genetics that focuses on the function of chromosomes in individual cells. McClintock’s work on chromosomes in maize revolutionised this field. In her time, she was widely respected, receiving a number of prestigious awards and fellowships, not least the National Medal of Science. However, it is her discovery of transposons – which revolutionised our understanding of genetics – that was entirely radical. Yet it took thirty years for the scale of her discovery to be fully acknowledged, with the award of the Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology “for her discovery of mobile genetic elements” in 1983 (NobelPrize.org).

A trademark of McClintock’s research was her unwavering attention to detail. Meticulous data analysis remains essential if one is to have confidence in one’s scientific hypotheses, and all the more vital if such assertions are novel and so question established ideas. Challenging the status quo is precisely what McClintock’s discovery of transposons achieved.

It was her thorough interrogation of the data that enabled her to have first confidence and eventually conviction as to what at that time seemed to be an unlikely – even implausible – scenario. In effect, her data showed that genes could be mobile, moving around the chromosomes, hopping from one place and re-inserting themselves elsewhere. McClintock discovered these peculiarly behaving genes whilst working on maize plants in the late 1940s. We now call these genes ‘transposons’, often aptly referred to as ‘jumping genes’. In November 1953 McClintock published her findings in the journal Genetics, with a paper entitled Induction of instability at selected loci in maize.

McClintock’s discovery did not sit comfortably with the twentieth century consensus as to how genes should behave. At the time, geneticists considered that genes were stable entities and the notion that there could be ‘renegade’ strands of DNA moving about the genome was treated with extreme caution. But if one places McClintock’s discovery in a broader social and historical perspective, given the nature of the proposal – that is, the idea that something which was perceived as stable, was actually subject to change – one could almost see the skepticism with which it was initially received as less surprising, maybe even predictable.

In some broad sense this might say something about a human desire for stability. If one looks back over the history of science it is not unreasonable to suggest that the scientific theories which met with the most vehement, almost visceral resistance were often those which are not only ‘big ideas’, but those which have championed ‘change’ in a previously accepted framework of ‘permanency’.

This is all the more true when it comes to natural phenomena that an individual cannot observe with the naked eye and/or witness over the course of their own short life-span. Notable examples include the idea of the Big Bang, and nearer to home that of continental drift; a proposal by the meteorologist Alfred Wegener who suggested (quite rightly) that Earth’s continents were once joined together and slowly drifted apart (and continue to move) over millions of years. From the time it was first proposed in 1912 the idea of continental drift found little favour and until the late 1960s the consensus remained that the Earth’s continents were static.

Another example is of course Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, which was proffered at a time when society at large was still committed to the notion of the permanency of species (i.e. that each species on Earth was created in its current form and was not the result of evolution). Here too, Darwin was correct, but some of the resistance stemmed from people who saw weaknesses in the theory, and ones that Darwin lost little time in addressing.

Pigmentation on corn kernels reveals the activity transposons (Image: Damon Lisch via Wikimedia Commons)

In the case of McClintock her work perhaps reflects more than a hint of our collective human condition inasmuch as although the existence and behaviour of transposons was relatively swiftly accepted by other geneticists who conducted research on maize, when it came to applying these ideas to other forms of life, not least humans, the implications were far more slowly accepted. In the case of transposons, interest in these small pieces of mobile DNA remained largely dormant until the 1970s when they were found in viruses and bacteria. From there, interest was ignited and further research revealed that transposons are found in most life-forms, including of course humans.

Let us leave the last words to McClintock. After receiving the Nobel Prize in 1983 she remarked: “You just know sooner or later, it will come out in the wash, but you may have to wait some time.” (quoted in McGrayne 2001, p.144)

Text copyright © 2015 Victoria Ling. All rights reserved.

References

McClintock, B. (1953) Induction of instability at selected loci in maize. Genetics 38, 579–99.

McGrayne, S.B. (2001) Nobel Prize Women in Science. Carol Publishing Group, Secaucus, NJ.

Pray, L. and Zhaurova, K. (2008) Barbara McClintock and the discovery of jumping genes (Transposons). Nature Education 1, 169.

Ravindran, S. (2012) Barbara McClintock and the discovery of jumping genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 109, 20198-20199.