Coming up for air

Within a few hours of the naval sonar drill, reports arrived of stranded beaked whales appearing over many kilometres along the coast. These animals showed signs of decompression sickness, also known as ‘the bends’.

Post-mortems on these animals revealed gas and fat bubbles in their bones and tissues.

The deeper you dive, the more the pressure forces nitrogen and oxygen from your lungs to dissolve into your body tissues. If you then surface too quickly, these gases can come out of solution and form bubbles in your blood. These can block smaller blood capillaries, cutting off the oxygen supply to the affected tissues. Decompression sickness is a recurrent risk amongst scuba-divers who breathe compressed air, and breath-holding ‘free-divers’ who make too many consecutive dives.

We have a diving reflex like other mammals. As the water hits our face, our heart slows and muscles under the skin contract, shunting blood into the centre of our body. Water pressure increases by 1 Atmosphere for every... more 10m depth. At 2 Atmospheres, the air in our lungs is half its original volume. By 50 metres (5 Atmospheres), gaseous oxygen and nitrogen dissolves into our body tissues, and fluid floods into our lungs. The human free-diving depth record is 214 metres (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

In contrast, beaked whales routinely hunt for an hour below 1000m, using echolocation. These ‘extreme divers’ do not normally experience decompression sickness, although fossils from early in their evolutionary history show that they were not immune to these problems. X-rays of the fossilised bones of more primitive whales show regions where bubbles formed inside a capillary, damaging the bone tissue and leaving a tell-tale signature.

Whale embryos initially develop rear limb buds, like land mammals. These structures are reabsorbed back into the body later in development. The fossil record, along with DNA studies, reveal that whales’ closest living relatives are cows and hippos, which share their same four-legged (tetrapod), hoofed, land-dwelling ancestors.

The hind limbs of this Spotted Dolphin embryo (Stenella frontalis) are visible as small bumps (limb buds) near the base of the tail. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

This raises some puzzling questions:

– Why did whales’ ancestors take to the water after 300 million years on land?

– Why didn’t they re-evolve gills?

– How can they dive for so long without getting ‘the bends’?

Why did whales’ air breathing ancestors take to the water?

These North Ronaldsay sheep are descended from an Orkney population farmed here since Neolithic times. They graze along the shoreline, feeding almost exclusively on seaweed. Their rumen stomachs have an adapted bacteria... morel population which enables them to digest marine algae (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The land-dwelling ancestors of whales may have first waded into the sea to escape from predators on land. Shallow coastal areas offered a relatively safe haven with little competition for the new food resources available in or near the water. This initial stage would have enabled these semi-aquatic ancestors of modern whales to adapt their digestive systems to a marine food source.

Fossils from the early Eocene (52Ma) show a succession of increasingly aquatic forms. From crocodile-like and otter -like amphibious hunters, developmental changes remodelled their breathing, senses, kidney function and limbs to survive better in water. By 40Ma, these early whales had flippers, a fluked tail, and could mate, birth and suckle their young without leaving the water.

At the Eocene-Oligocene boundary (around 36Ma), movement of the continental plates opened up the deep waters of the circum-Antarctic ocean. This offered new ecological roles for the deeper-diving whales. Many new whale species appeared, including ancestors of the filter-feeding baleen whales and toothed whales that hunt in deep waters using echolocation.

Why didn’t whales re-evolve gills?

A sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) begins a dive; Gulf of Mexico. Adaptations for cold, deep waters include insulating blubber, lungs designed to collapse under pressure, and locomotion. The fluked tail is a super-e... morefficient ‘caudal oscillator’; both the up and down strokes generate lift, like a birds’ wing. These and other whale and seal species dive deep both to forage and to escape from killer whale (Orcinus orca) attacks (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The ability to breathe underwater like fish seems at first like a requirement for life in the sea. However despite their lack of gills, whales and dolphins are highly effective predators in both shallow and deep water.

Modern whales’ warm bodies enable their fast reflexes for hunting. Whilst swordfish and tuna have some warm muscles, most of their tissues are at sea water temperature. Were their whole bodies warm, the heat loss from their gills would be energetically too costly.

Fish gills develop from the ‘branchial arches’; bulging structures in the early vertebrate embryo. These same tissue bulges give rise to the lower jaw, the middle ear, hyoid bone and larynx in the throat of humans and other mammals. For whales and other mammals to form gills would require that they develop new embryonic structures; this would render redundant the lungs with their vast area of vascular tissue.

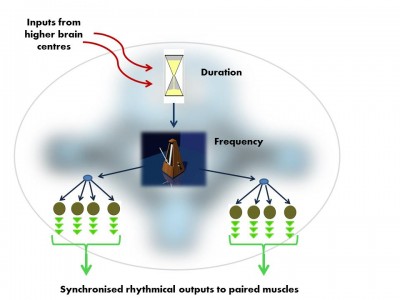

Breathing air enables whales to use vocal signals to coordinate their social groups and attract mates. Like land mammals, the baleen whales make vocal calls by passing a controlled air flow through the larynx. Echolocation, the alternative means of producing sound used by dolphins and other toothed whales, also requires air. Their ‘sonic lips’ generate calls in an air-filled nasal passage. Whilst many fish make sounds, their vocal abilities are simple and limited.

How do they dive for so long without getting ‘the bends’?

This diagram shows how myoglobin forms ‘alpha-helical’ spirals around a ‘haem’ co-factor. Haem’s ring-structure holds an iron atom, carrying an electrostatic charge. This attracts and holds an oxygen molecule ... more(red spheres). As carbon dioxide builds up it dissolves to form carbonic acid. This change of pH, alters the electrostatic balance, prompting myoglobin to release its oxygen. The myoglobin protein’s high positive charge also steadies the pH when cells break down sugars without oxygen and produce lactic acid (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

All mammals store oxygen in their muscles using a protein called myoglobin. Sustained activity during long foraging dives requires a lot of oxygen. Deep divers have much higher muscle myoglobin concentrations than land mammals, giving them substantial oxygen reserves.

Modern diving mammals, and deep diving fish such as tuna, have also modified their myoglobin. As early whales began to explore the deeper waters, selection resulted in better survival from individuals whose myoglobin carried a stronger positive electrostatic charge. Like positive magnetic poles, these ‘supercharged’ molecules repel each other. This keeps them in solution, allowing them to function at high tissue concentrations where most other proteins would clump together.

A supercharged form and high concentration of myoglobin makes it possible for deep diving mammals to return to the surface slowly after a prolonged dive. This behaviour avoids decompression sickness.

However when beaked whales and other species encounter naval sonar at depth, this causes them to ‘panic’ and surface too quickly, inducing ‘the bends’.

Text copyright © 2015 Mags Leighton. All rights reserved.

References

Balasse M et al. (2006) ‘Stable isotope evidence (δ13C, δ18O) for winter feeding on seaweed by Neolithic sheep of Scotland’ Journal of Zoology 270(1); 170-176

Beatty B L & Rothschild B M (2008) ‘Decompression syndrome and the evolution of deep diving physiology in the Cetacea’ Naturwissenchaft 95;793-801

Costa D P (2007) Diving physiology of marine vertebrates’ Encyclopedia of life sciences doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0004230

Ferguson S H et al. (2012) ‘Prey items and predation behavior of killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Nunavut, Canada based on Inuit hunter interviews’ Aquatic Biosystems 8 (3); http://www.aquaticbiosystems.org/content/8/1/3

Gatesy J et al. (2013) ‘A phylogenetic blueprint for a modern whale’ Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution’ 66:479-506

Mirceta S et al. (2013) ‘Evolution of mammalian diving capacity traced by myoglobin net surface charge’ Science 340;1234192

Nery M F et al. (2013) ‘Accelerated evolutionary rate of the myoglobin gene in long-diving whales’ Journal of Molecular Evolution 76;380-387

Noren S R et al. (2012) ‘Changes in partial pressures of respiratory gases during submerged voluntary breath hold across odontocetes; is body mass important?’ Journal of Comparative Physiology B 182;299-309

Orpin C G et al. (1985) ‘The rumen microbiology of seaweed digestion in Orkney sheep’ Journal of Microbiology 58(6); 585-596

Rothschild B M et al (2012) ‘Adaptations for marine habitat and the effect of Jurassic and Triassic predator pressure on development of decompression syndrome in ichthyosaurs’ Naturwissenchaften 99;443-448

Steeman M E et al. (2009) ‘Radiation of extant cetaceans driven by restructuring the oceans’ systematic biology 58;573-585

Thewissen J G M et al (2007) ‘Whales originated from aquatic artiodactyls in the eocene epoch of India’ Nature 450;1190-1195

Thewissen J G M et al (2006) ‘Developmental basis for hind-limb loss in dolphins and origin of the cetacean body plan’ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 103(22); 8414–8418

Thewissen J G M and Sunil B (2001) ‘Whale origins as a poster child for macroevolution’ Bioscience 51(12);1037-1049

Tyack P L (2006) ‘Extreme diving of beaked whales’ Journal of Experimental Biology 209;4238-4253 Naturwissenchaften 99:443-448

Uhen M D (2010) ‘The origin(s) of whales’ Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 38;189-219

Uhen M D (2007) ‘Evolution of marine mammals; back to the sea after 300 million years’ The Anatomical Record 290;514-522

Williams T M (1999) ‘The evolution of cost efficient swimming in marine mammals; limits to energetic potimization’ Philosohical Transactions of the Royal Society of London series B 354;193-201