What’s so different about human speech?

Upon leaving the island, Odysseus is warned that storms lie ahead. His route home to Ithaca passes the sirens; monsters whose beautiful, haunting voices lure sailors to their deaths.

He sets a course and explains his intention to the crew. At his command they fasten him to the mast, seal their ears with wax, and prepare for their encounter.

They reach treacherous waters. The siren song reaches into Odysseus’ mind, resonating with his deepest longings. The storm rages within. He struggles, but his bindings, the result of his clear intention, secure him tightly to the mast.

Forced to stand still and listen, he finds that he starts to hear the voices for what they really are; the empty fears of his own soul. He relinquishes his fight and hears the voice at his own still centre. The storm calms.

The crew notice that he has returned to his senses. They cut him loose.

He is indeed a wise and worthy captain.

This ancient footprint, first made in soft mud, is an index which shows us the passing of an three-toed Theropod dinosaur. Denver, Colorado (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Speaking involves transmitting and interpreting intentional signs, some of which are also used in the instinctual communications of animals. These signals are of three kinds: 1. An index physically shows the presence of something, e.g. wolves tracking their prey by scent.

2. An ‘icon’ resembles the thing it stands for, like a photograph or a painting. Dolphins, apes and elephants recognise their own reflection; we assume that they interpret this two-dimensional image as representing their three-dimensional physical selves.

3. A symbol associates an unrelated form with a meaning. Our words are symbols, linking an idea with unique sound-and-movement sequences. They do not resemble the things they represent.

The ‘Union Jack’, a symbol of Great Britain since the union of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801. It is made up of three other flag symbols; the Cross of St George for England (insert, top), St Andrew’s Saltaire f... moreor Scotland (centre), and for Northern Ireland, St Patricks Saltire (below) (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Symbolism is almost unknown amongst animals, with a few rare exceptions. A stereotypical form of symbol is the ‘waggle dance’ of honeybees.

Although chimpanzees can be taught to use some sign gestures, they do not naturally communicate using symbols. In contrast, we use our symbolic language intentionally.

Our uses of speech are unique. We revisit our memories, order our thoughts and make future plans. With a destination in mind, we can listen for our ‘inner voice’, map out our route, take a stand against the storm of inner and outer distractions, and find our way home.

How is our speech unique?

Normal speech is already multi-channel; our words are accompanied by the musicality of our speaking, and our facial expressions and other physical gestures transmit many layers and levels of complex meaning. Writing is ... moreanother mode of communicating our language. Social media transmits our language into virtual worlds. The online social networking service Facebook commissioned ‘Facebook Man’ to commemorate their 150 millionth user(Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Aspects of our language ability are found in other animals, but the way we have combined and developed these traits is uniquely human.

1. We use any available channel.

Most human languages use vocal speech. Under circumstances where speaking is not possible, we find other ways, e.g. sign languages and Morse code.

2. We build our words from parts that gain meaning as they are combined

Most of the syllables we use to build words lack meaning on their own. Combining them together (as in English) or adding tonal shifts (as in Chinese) creates words.

3. We code our words with meanings, making them into symbols

The chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) known as Washoe (1965-2007) was the first non-human animal to be taught American sign language. She lived from birth with a human family, and was taught around 350 sign words. It was rep... moreorted that upon seeing a swan, Washoe signed “water” and “bird”. Chimpanzees are capable of learning simple symbols. However Washoe did not make the transition to combining these symbols together into new meanings (Image: Wikimedia commons)

Symbols are ‘displaced’, i.e. they do not need to resemble the thing they represent. Our words symbolise ideas, experiences and things.

4. We combine these symbols to make new meanings.

We build words into phrases and stories, use these to revisit and share our memories, combine them into new forms, and communicate this information to others in various ways. Combining different symbols brings us a new understanding, which changes how we respond.

Look at this painting. As you do, consider what feelings it provokes.

‘Wheatfield with crows’ by Vincent Van Gogh, 1890. (Image; wikimedia commons)

It is, of course, by Vincent Van Gogh. As you may know, his choices of colour and subject material were a personal symbolic code. He often used vibrant yellows, considering this colour to represent happiness.

His doctor noted that during his many attacks of epilepsy, anxiety and depression, Van Gogh tried to poison himself by swallowing paint and other substances.

As a consequence, he may have ingested significant amounts of toxic ‘chrome yellow’, which contains lead(II) chromate (PbCrO4).

Now consider this statement.

“This is the last picture that Van Gogh painted before he killed himself” (John Berger 1972, p28)

Look again at the picture.

What do you feel this time?

‘Wheatfield with crows’ by Vincent Van Gogh, 1890. (Image; wikimedia commons)

Certainly our response has changed, though it is difficult to articulate precisely what is different. The image now seems to illustrate this sentence. Its symbolic content has altered for us. This example shows how combining two types of information –an image and text- can change the meaning it symbolises.

Some animals can be trained to recognise simple symbols. The psychologist Irene Pepperberg taught her African Grey parrot ‘Alex’ to count; he learned to use numbers as symbols, and could identify quantities of up to 6 items.

An African Grey Parrot (Psittacus erithacus). Professor Irene Pepperberg’s parrot, Alex, learned basic grammar, could identify objects by name, and could count (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

5. The order in which we combine symbols defines their meaning

We put word symbols together into phrases, sentences, descriptions, sayings, stories, poems, documents, manuals, plays, oaths, promises, parodies, plays, pantomimes….

The ordering of words follow rules (grammar and syntax). Animals such as dogs and dolphins show some form of syntactical ability, but there is no evidence that they are on the verge of using what we understand as language. The order of words shows us their relationship, allowing us to understand how they are interacting. We change the order of our words and phrases to change the meaning we wish to communicate.

For instance; this makes sense.

‘Jane asked Simon to give these flowers to you.’

This doesn’t quite fit our normal understanding of reality…

‘These flowers asked Simon to give Jane to you.’

This works, but the meaning has changed.

‘Simon asked you to give these flowers to Jane’

However grammar is not enough . The words in combination need to ‘make sense’ for us to understand the meaning the speaker wishes to communicate.

What does this enable us to say?

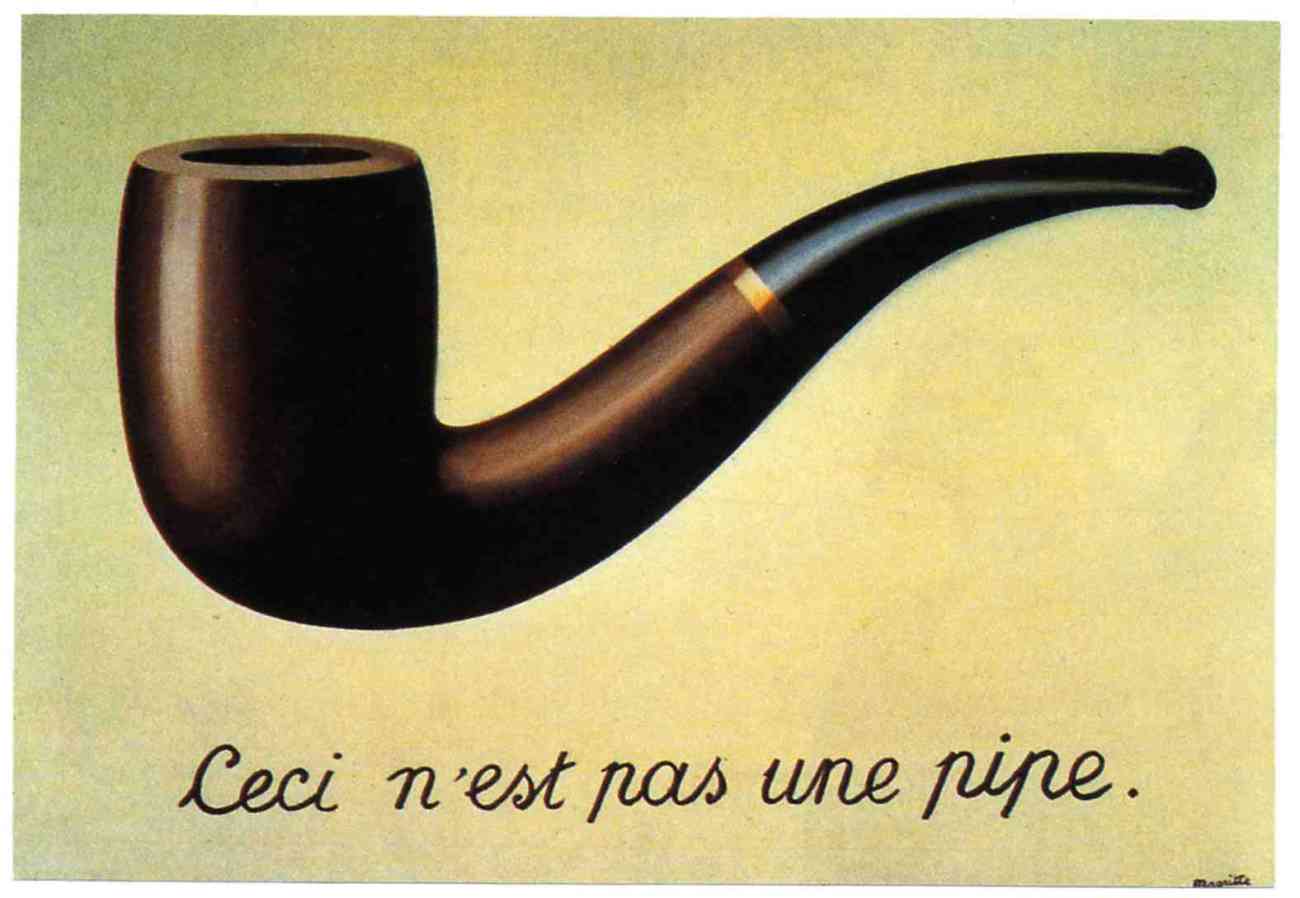

‘The treachery of images’ by Belgian surrealist painter, Rene Magritte (1928-9).Much of Magritte’s work explored the combination of words and images, and the way that this challenges the meaning that we understand... more from the components on their own. This combination of words and image have been deliberately chosen so that they contradict each other.What the artist says is true. However, it isn’t a pipe! It is a two-dimensional representation of a pipe (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

When we make new combinations of words, or add words to a visual signal such as a gesture, we create a new meaning.

We can add adjectives to a description, add qualifiers, combine phrases into a sentence, and make statements one after the other so that our listener associates these ideas. This process is known as ‘recursion’, a linguistic term borrowed from mathematics.

Our ideas about time vary between cultures, but we all mentally ‘time travel’ by revisiting our memories. For instance, the scent of something can evoke a memory that transports us back into an earlier event; suddenly we experience again the emotions and sensations we felt at that time. Putting our current selves into the past memory, or imagining a future scenario and inserting ourselves into that story, is a form of recursion.

Memory allows us to link speaking and listening with the meanings of our words. Our language is well structured to easily express recursive ideas. This shows us that our thinking uses recursion.

Why are we able to do this?

An illustration by Randolph Caldecott (1887) for ‘the House that Jack Built’. This traditional British nursery rhyme uses recursion to build up a cumulative tale. The sentence is expanded by adding to one end (end r... moreecursion). Each addition adds an increasingly emphatic meaning to the final item of the sentence (i.e. the house that Jack built) (Image: Wikimedia Commons). One final version of combined phrases ends like this;This is the horse and the hound and the hornThat belonged to the farmer sowing his cornThat kept the cock that crowed in the mornThat woke the priest all shaven and shornThat married the man all tattered and tornThat kissed the maiden all forlornThat milked the cow with the crumpled hornThat tossed the dog that worried the catThat killed the rat that ate the maltThat lay in the house that Jack built.

Our thinking capacity, through which we learn and remember, means that we can copy and learn to use language. Although some brain regions appear specialised for roles in memory and language, our ‘language function’ uses our entire brain, and cannot be dissociated from our minds.

Our ‘language brain’ includes the ‘basal ganglia’; these are neurons which connect the outer cortex and thalamus with lower brain regions.

We need this connectedness to coordinate movements in our fingers, to understand the relationships between words that are inferred by their order in our phrases, and to solve abstracted (theoretical) problems. This network interacts with ‘mirror neurons’ which allow us to relate to and decode the posture, speech and emotional cues of others.

The basal ganglia that influence our speech also regulate the muscles controlling our posture. Standing is therefore more than just balancing on two legs; it is a whole body activity and requires much finer muscle control than walking on all fours. It also frees the hands, which allows us to manipulate tools. Lieberman suggests that it is the fine motor control required to maintain our upright posture which pre-adapted our ancestors for manipulating hand tools as well as the tongue, lips and other structures that make speech possible. This upright posture is linked with a remodelling of our breathing apparatus, giving us more control over our larynx.

Philip Lieberman’s work with people suffering from Parkinson’s’ disease suggests that it is the ability to remember that makes speaking possible. Parkinson’s patients have degraded nerve circuits in their basal ganglia, so these patients have short term memory problems and difficulties with balancing and making precise finger movements. They also struggle with understanding and using metaphors and longer word sequences. This suggests that when we speak we are using the circuitry for sorting and remembering movement sequences, irrespective of whether these are producing words or actions.

Our posture has remodelled the evolution of our entire physiology from breathing to childbirth. It frees the hands, allowing us to perform delicate and precise sequences of tasks. Selection for the ability to precisely ... moresequence our manual motor skills may have provided our ancestors the means to better sequence their thoughts (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

The basal ganglia that influence our speech also regulate the muscles controlling our posture. Standing is therefore more than just balancing on two legs; it is a whole body activity and requires finer muscle control that walking on all fours. It also frees the hands, which allows us to manipulate tools.

Lieberman suggests that it is the fine motor control required to maintain our upright posture which pre-adapted our ancestors for manipulating hand tools as well as the tongue, lips and other structures that make speech possible. This upright posture is linked with a remodelling of our breathing apparatus, giving us more control over our larynx.

The nerve networks that control our limbs and voices are linked across all vertebrates. Our basic ‘walking instinct’ initially activates Central Pattern Generator circuits driving movement in all four limbs. These are the same neural outputs that control our lips, tongue and throat.

Conclusions: What does this say about our language?

Captain Odysseus stands upright against the mast. This posture is distinct to our species, and has many implications for our speech, language and other actions

(Image: Wikimedia commons)

- Our hominin ancestors evolved to use symbolic words and stories as a code to store and share memories, develop new skills and ideas, and coordinate their intentions and actions with their tribe.

- When we revisit our memories or ‘reword’ our experiences into new sequences, we remodel the past, and project our thoughts into the future.

- The control we have over our vocal sounds is linked with our neural circuits for movement. The ability to balance ideas and manipulate our tongues is linked to our ability to stand upright, balance on two feet and manipulate tools with our hands.

- Language, then, is a cultural tool that allows us to order our thoughts, go beyond our instincts, share our intentions, and choose our own story.

Text copyright © 2015 Mags Leighton. All rights reserved.

References

Berger J (1972) ‘Ways of Seeing’ Penguin books Ltd, London, UK

BickertonD and Szathmáry E (2011) ‘Confrontational scavenging as a possible source for language and cooperation’ BMC Evolutionary Biology 11:261 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-261

Corballis MC (2007) ‘The uniqueness of human recursive thinking’ American Scientist Volume 95 (3), May 2007, Pages 240-248

Corballis, M.C.(2007) ‘Recursion, language, and starlings’ Cognitive Science 31(4) 697-704

Everett D (2008) ‘Don’t sleep, there are snakes: Life and language in the Amazonian jungle’ Pantheon Books, New York, NY (2008)

Everett, D (2012) ‘Language: the cultural tool’ Profile Books Ltd, London, UK

Gentner TQ et al (2006) ‘Recursive syntactic pattern learning by song birds’ Nature, 440;1204–1207