Many animals produce song, but for one species, the vocal repertoire stands out as remarkable. Their calls, specific to their social group, combine a basic set of sounds into endlessly varied combinations. These are enhanced by altering rhythm, pitch and stress, and are complimented by gestures, sometimes using the entire body.

These calls transmit sophisticated information. The meaning of each compound sound depends upon its position within their song-like phrases. Each phrase is complex, and meaning is added to when phrases are combined.

Making these vocal calls requires the coordination in sequence of some 40 muscles in the mouth and throat. But there is one snag; the vocal anatomy which allows these animals to articulate their calls also predisposes them to a high risk of choking.

And to observe one of these extraordinary creatures, look in a mirror. Meet Homo sapiens; sound-smith, toolmaker, storyteller.

The possession of speech is the grand distinctive character of man“

[Thomas Huxley, 1871]

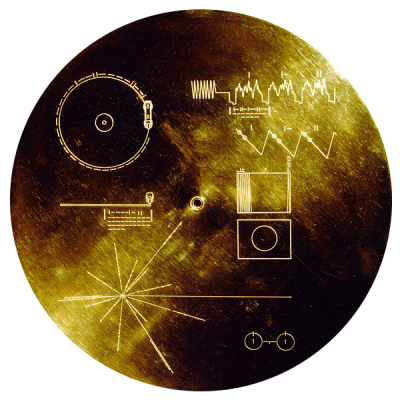

The NASA Voyager 1 space probe, launched in 1977, is now approaching the outer reaches of our solar system. On board, a gramophone record provides a selection of natural and man-made sounds from earth. These include mus... moreic from different genres and greetings to the Universe in 55 of earth’s different languages. The cover, shown here, indicates how to play the recording (Image: Wikimedia Commons). To listen to the earth sounds sent into space, click here.

We enjoy a unique legacy; language. This is paradoxical; the physical attributes that together make our speech possible are not exclusive to humans, although evolving our particular combination of them is indeed novel, as are its consequences. Our habit of communicating by speaking has re-structured our entire ecology.

Speech sets us apart, defines how we understand ourselves, and codes our behaviours and habits. Through language we cooperate, adapt to our circumstances, share and use knowledge, coordinate our behaviour with others, align our actions with our intentions, and reach outacross the boundaries of time and space.

“We are more alike, my friends, than we are unalike” (Maya Angelou)

Language then, appears to define who we are. This opens up many questions.

How can we define language?

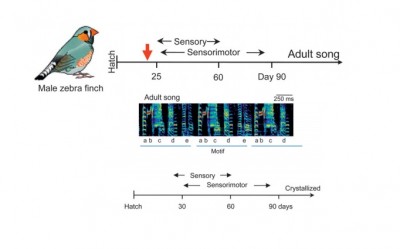

Male zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) learn their courtship song in stages. During the ‘sensory phase’ juvenile birds listens to birds in their environment. In the sensorimotor phase, it starts to ‘babble’; a... morettempting copied versions of the song (the ‘sub song). Later the bird begins to generate subtle variability within highly structured syllables (as shown on the sonograph – letters refer to sound syllables). At sexual maturity the song ‘crystallises’ (i.e. becomes fixed) into its adult song form. This can be very similar to the original tutor’s song (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Language is a human-made tool that fulfils specific needs. A biologist would regard speech as a behaviour which is integrated into how the body works, and which enabled our ancestors to survive better. We are proof that this is so. For speaking to have evolved implies that our current form of language behaviour arose and was refined gradually through natural selection.

Language, like our other complex behaviours, is learned. Children do not learn to speak without contact with other humans. Our language skills develop into adulthood and change continuously; we are always acquiring and using new words.

Other animals and birds that learn complex forms of song have a sensitive period for learning these calls (the ‘imprinting period) which reduces substantially as they mature.

Whether ‘imprinting’ also applies to humans is controversial. We cannot easily assess whether an adult student, meeting a new language starts from the same basis, is exposed to the same amount of data as a child acquiring their first language. Also their reasons for learning are different; children are building a sense of identity as they grow their speaking capacity. This difference affects how people learn at different stages of their lives.

The case of Kaspar Hauser gives us some insight. This boy first encountered language in his teens. When later enough vocabulary had been acquired, he was able to describe some of his earlier life, indicating that he was able to ‘think’ before he could speak. However he never fully mastered grammar. It is this additional level of word ordering that allow us to sort and structure our thoughts.

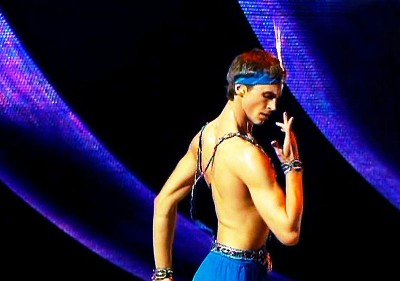

The efficiency of the brain in handling language is moulded by experience. Many of the language functions use same brain networks as are needed by musicians when playing an instrument. People trained in music from a you... moreng age have superior language abilities compared to non-musicians (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Most likely, the sophisticated songs of some birds, dolphins and certain other social mammals are driven by sexual selection. So too is the descent of the larynx in human males at puberty, which affects the pitch of their voice. This suggests that human vocal calls have been important for mate choice at some stage in our evolution. However our main vocal differences, revolving around vocal pitch and tone, mostly reflect the individual’s body size. We have no gender bias in our capacity for speech, suggesting that selection for language provided our ancestors with group-wide survival benefits.

Although we can assume that language-based survival advantages have driven the evolution of our sound-making apparatus and the mental processes that we use for speech, language also codes information that we inherit. Crucially, this is independent of our genetics. Selection for access to this cultural information acts at the level of our social group. It has crafted us into a diverse population of accomplished makers and sharers of sound, movement and meaning.

What does our language enable us to ‘do’?

i. We express the contents of our minds through physical movement

Andrey Ermakov performing the character ‘Ali’ in the ballet Le Corsaire (The Pirate); July 17, 2012. Ballet is a dance tradition using a repertoire of stylised moves. Within the Chinese ballet tradition, as well as ... morethe overall production playing a storytelling role, the stylised movements of the dance themselves carry complex meanings which are important for storytelling. This used to be also part of the ballet tradition in western Europe, but faded from the tradition after the mid 19th century (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

We speak by moving our bodies in a way that generates signals in one or more communication modes. Although we tend to conform to our group’s agreed use as to what words mean, we make this ‘dance’ of stylised gestures our own. The sound of our voice, like the way we walk, and even the way we sign our name, is individual, distinctive and recognisable.

ii. We order our thoughts (and actions) into sequences

Often we mentally list our tasks, and imagine carrying them out in a specific order before we act. In this way, we use language to define, structure and plan out our experience.

iii. We code our experience with meaning

We share an understanding of word meanings with other users, although we code that meaning individually. Thinking of a phrase, such as ‘moved to respond’, activates the mirror neuron network. This maps our physical and emotional understanding of the words onto relevant areas of our brain, in particular the sensori-motor cortex and limbic system. Our internal coding of words depends upon the emotions we tag to our memories, and relates us to a physical, ‘embodied’ experience of their meaning. iv. We shift our awareness between details and concepts

Hawaiian petroglyphs from the Big Island.Symbolic content carries meaning at different levels.In the traditional Huna language of Hawaii, words have meaning at different levels. The word ‘huna’, literally translated... more, means ‘secret’. Broken into syllables, ‘hu’ refers to ‘male’ or ‘active energy, and ‘na’ is ‘female’ or ‘passive’ energy. The word also has a higher meaning of ‘hidden, esoteric knowledge’ (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

When we turn a verb into a noun (e.g. speaking becomes ‘speech’) we have generalised an action idea into a more abstracted form. This assigns a symbolic understanding to the new word. As we relate them, our experiences become coded as concepts and metaphors; in this way big ideas are put into words. We also code meaning through sayings and stories.

v. We define our reality in various ways.

Ever heard of ‘performatives’? These are a special class of verb whose utterance changes our circumstances.

– When a judge declares ‘I sentence you to life imprisonment’, this statement alters the course of the life of its recipient in the dock.

– Oaths, e.g. marriage vows, are performative statements. These declarations of intention commit us to a voluntary long lasting change in our behaviour.

– Coining or learning new words brings these new ideas into our consciousness. This opens up new possibilities and affects how we respond to our circumstances. Our values, the things that are important to us, inform the beliefs we hold around our sense of self, and affects the way we derive meaning from our experiences. We internally translate our beliefs and values as presuppositions, i.e. what we assume is true about our world. These define what we allow ourselves to think, inform how we behave, and determines how we respond to and evaluate our circumstances.

vi. We visit experiences outside of the present moment

The TARDIS, which looks like a police phone box from 1950’s Britain, features in a popular and long-running UK TV series called Doctor Who. Its main character, ‘The Doctor’ uses this vehicle to travel in time and ... morespace. The Doctor periodically reinvents himself, as has the TV series (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

When we re-live our memories, and access the memories of others, we ‘travel’ in time and space. As we re-visit our memories, our past thoughts reappear in the present moment, and in a different location. Telling others about something allows us to journey with them through the story.

Typically we mention only the important details; this filters the narrative for its meaningful events. Telling a story in a different way, or altering the sequence of events in a tale, can alter how we feel about and relate to these events. This ‘reinvention’ changes their meaning.

viii. We become more like each other as we connect through language To have a conversation, we accept a shared understanding of meaning of our words, how we order them into phrases, and the beliefs and values that are coded into the expressions we use. By ‘speaking the same language’, we connect with and accept a ‘cultural norm’.

For language to have had a selective advantage, the benefits of conforming to the behaviour of our cultural group must have outweighed the reproductive success of being a ‘maverick’. We are living proof that this symbol-based group communication system works. Choosing group cooperation through collective action enhanced the survival of our ancestors.

Does this define how we think?

The Thinker by Auguste Rodin, at the Legion of Honour, San Fransisco. This is one of a number of over-life size bronze casts based on the twenty seven inch high original version, made for the Paris exhibition of 1889 (W... moreikimedia Commons)

Asking ‘how does language enable us to think?’ presupposes that thinking involves language. This constrains what we might think of as ‘thinking’. ‘Thinking’ can and does take place without speech. If we focus our attention to listen to or look at something, we are directing our actions and thoughts without using language. Presumably animals ‘think’ in this way.

Language, however, takes us into a different mental mode from animal thinking. We use words to articulate the contents of our own minds to ourselves. Words link meaning with sounds, gestures or images that need not bear any relation to what they symbolise. Accordingly, we are the only animal capable of coding meaning into symbols and communicating our understanding through how we combine them.

A very few species of animals, e.g. dolphins and elephants, can recognise themselves in a mirror, as demonstrated by the way in which they use this reflection to examine a mark placed out of sight on their body. This implies that they understand the difference between ‘self’ and ‘other’ (a ‘theory of mind’).

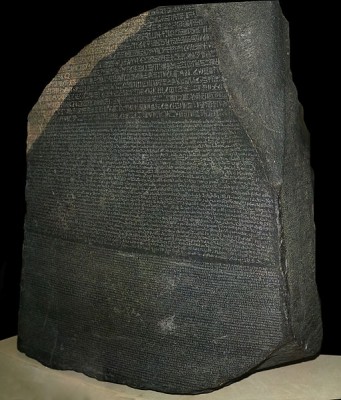

Any communication, whether written or spoken, codes information and meaning which must be understood by both the sender and receiver of the message. The Rosetta Stone, originally from an ancient Egyptian temple (~196BC)... more shows parallel texts in ancient Egyptian, Demotic (an ancient language from the Nile Delta) and ancient Greek. This ‘cipher’ enabled scholars to decode and translate ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

When we ‘think’ about something, it goes beyond what we see, hear and feel. Information is processed by the unconscious mind. This then presents our conscious mind with a constructed representation of what we perceive, tagged with an emotion which codes meaning into the content of the thought. The way we build this internal world is affected by both our personal perspective, and our shared cultural experience.

Words define what we think something is, and therefore also what it is not. This frames our awareness of it, creates boundaries around what we perceive, and directs the level of attention we give it. Questions frame our choices to a reduced number of alternatives (“Is it this, that, or even those?”). This limits the number of possible outcomes. However we define thinking, we are the only animal capable of thinking about thinking. This is a unique feature of human language, and idea underpins Descartes’ famous phrase;

I think, therefore I am

What do we think about language?

Studies of language have varied between two viewpoints which highlight a bigger question: how we think about our physical selves. The ‘classical’ view of self thinks of the body as functioning separately from the mind (a ‘mind-world’ perspective). Thinking of our language in this way leads us to suggest that our ability to speak develops ‘innately’, much like our limbs and kidneys, and presumably through a genetically controlled process. In the 1960’s Joseph Greenberg suggested that in all human languages. words like nouns and verbs play similar roles. Noam Chomsky then developed this idea into his ‘theory of language’, suggesting that all human languages have a similar basic structure, which he calls a ‘universal grammar’. His framework has provided the starting point for a systematic study of what human language is.

This map (by Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, 1994) shows the generalised genetic relationships between human populations worldwide. Chomsky’s approach to language infers that our linguistic diversity is like our genetic di... moreversity.Genetic differences can appear vast, but we are one interbreeding population and at the level of our genes, we are much more alike than we are unalike (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Chomsky’s ‘universal grammar’ presupposes that all human languages are much the same. In this model, differences in vocabulary and word order are seen as ‘parameters’ (characters), and that any language is built from a subset of these characters. He has famously suggested that:

“…if a Martian was looking at humans the way we look at, say frogs, the Martian might conclude that there’s fundamentally one language with minor deviations.”

The Chomskyan view suggests that variations between languages, like the ordering of nouns and verbs, represent a limited set of choices. In this scenario, it is proposed that a child learning its first language would select from these choices through a genetic or developmental mechanism, triggered by the language input they receive. This idea is reminiscent of bio-genetic switches which ‘shuffle’ between genes, e.g. those that encode how quickly a virus induces symptoms in its host. This would imply that our children ‘look for’ cues to indicate which word order setting they need to ‘activate’ at the genetic level.

| Frequency distribution of word order in languages, after Tomlin (1986) p22. S = ‘Subject’ (noun performing the action in the phrase), O = ‘Object’ (noun acted upon), V = ‘verb’ (the action which is performed). | |||

| Word order | Short clause equivalent in English | Proportion of world languages with this pattern | Examples |

| SOV | “She him hears.” | 45% | Japanese, Latin, Turkish |

| SVO | “She hears him.” | 42% | English, Mandarin, Russian |

| VSO | “Hears she him.” | 9% | Hebrew, Zapotec, classical Arabic, Irish, Welsh |

| VOS | “Hears him she.” | 3% | Malagasy, Baure |

| OVS | “Him hears she.” | 1% | Apalaí?, Hixkaryana? |

| OSV | “Him she hears.” | <1% | Warao |

What might these cues be? The three-word ‘short clause’ is perhaps our simplest form of syntax, and is present in every language. In this phrase an item (the subject noun, S) acts on another item (the object noun, O) and the nature of that action is indicated by the verb (V), e.g. ‘scissors cut paper’ is SVO. Across the world’s languages, these words are used in all of the possible orders. However some of these forms are rare.

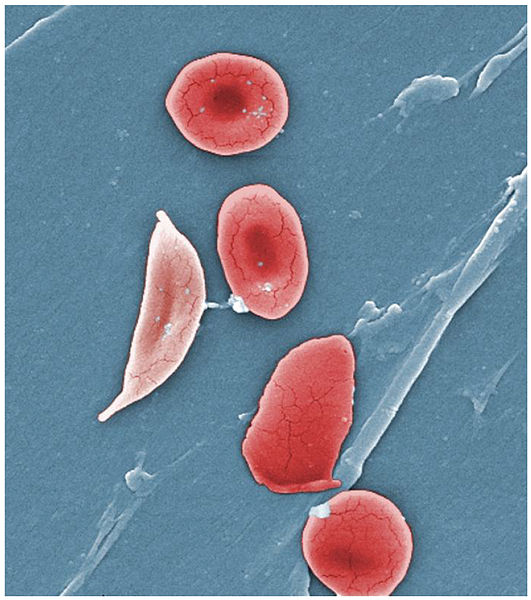

This uneven ratio of word ordering is reminiscent of the different ratio of forms (alleles) known for some genes. For example, genes encoding subunits of haemoglobin are found in almost all vertebrates, some invertebrates, and even some plants. Haemoglobin is found in our red blood cells; it binds oxygen at the high concentrations in our lungs, and releases it elsewhere in the body. Various forms of globin genes exist.

An artificially coloured scanning electron micrograph of red blood cells from a sickle cell anaemia sufferer. The red blood cells become crescent-shaped (sickle shaped) at low oxygen concentrations. The mutation in the ... morebeta-globin gene that causes this condition is more common in populations from malaria-prone regions. Malaria parasites invade red blood cells and reproduce asexually; this progresses more slowly in sickle cells, reducing the severity of the disease for the human sufferer, and increasing their chances of surviving the infection (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Most of us carry two ‘normal’ copies of the beta-globin gene (HbB) on chromosome 11, one on each of our chromosomal pair i.e. HbB/HbB. The HbS allele causes sickle cell disease (a form of anaemia) when one gene copy is present (i.e. HbB/HbS). Two HbS copies are lethal; not surprisingly, this keeps the mutation at a low frequency in most populations. However in West Africa, where malaria is a major scourge, 25% of individuals are HbB/HbS. The sickle cell condition provides some resistance to the malaria parasite, hence selection in this local population has acted to maintain this gene at a higher frequency.

Does selection in this way also apply to language structure? There is no clear indication that it does; there seems to be no obvious situation that favours some short clause options over others. After all, they all perform their function equally well. If word order had a genetic basis but no selective advantage, we would expect a more even distribution of forms in our languages worldwide. In practice, the form of a language’s short clause depends upon the cultural family from which that language arises.

Far from having a genetic basis, this view anchors grammatical structure to its history and circumstances. Nicholas Evans and Stephen Levinson have shown that the main characteristic of human communication worldwide is not its commonality, but its variation. Language forms vary so radically that in reality they find ‘vanishingly few universals’. Instead, human speech is characterised by its diversity in all aspects of its production including sound, meaning and syntax.

Whilst it seems that the grammar and syntax of language have no genetic basis, still we must have evolved our current capacity language. Our language function requires a physical means to produce the diversity of human speech sounds, and a cognition that allows us to think about what to say and understand what others are saying. These physical and mental capacities are not separate. Darwinian selection acts on whole bodies, meaning that language evolution, like the neural coding of our speech, is an ‘embodied’ process.

Philip Lieberman’s work has focussed on how the physical apparatus required to produce our speech may have arisen. He suggests that increases in the potential diversity of our ancestors’ speech signals were made possible by changes in their vocal tract, which were required to adapt their breathing and balance to fit an increasingly upright posture and bipedal locomotion.

A watchmaker at work. The watchmaker’s craft uses a degree of fine motor control and hand-eye coordination which is unprecedented in the animal kingdom (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Maintaining our posture would have required better fine motor control of the muscles used for balancing, breathing and eating, and also freed the hands, enabling better manipulation of tools. Chimpanzees do not have our levels of fine motor control. Producing sequences of actions involved with using manual tools have similar cognitive requirements to producing ordered sequences of speech sounds. In essence, evolving to ‘stand on our own two feet’ may have taught us to coordinate not only our walking but also our hand and finger movements, our voices, and possibly our thinking.

When we communicate, we physically relate to each other’s internal world through the actions of our mirror neurons. The chemical messages that these and other nerve cells use to ‘talk’ to each other are also recognised and produced by the cells of our immune system. In addition, our gut produce these same neurological chemicals as are found in the brain. This shows us that at the level of these information-carrying molecules, our mind and our physical body are in practice a single entity (a ‘body-mind’). This body-mind interacts with its environment, and changes biochemically according to the food we eat, the air we breathe, what we choose to think, and the company we keep.

Daniel Everett ’s lifetime study of the Pirahã people from the upper Amazon provides clues as to how our culture and language fit us to our environment. The Pirahã value self-reliance and eye-witness experience. They avoid assimilating non-Pirahã words into their language because they consider their traditional ways to be superior. They never combine their short, one-verb sentences into longer phrases (meaning they lack ‘classic’ Chomskyan recursion ), although they do combine ideas recursively by using sentences together. They use only a minimal form of past tense, and lack a mythology and a concept of numbers. Yet their cultural knowledge and attitude equips them to survive easily for many days in the jungle, as Everett puts it, ‘…equipped with only their wits and a machete’.

Goosebumps! This is body language for ‘I feel cold/scared/excited, and perhaps other meanings, according to context (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Viewing ourselves as a ‘body-mind in a context’, we see that local conditions define how we must behave in order to survive. Language in this sense is a cultural tool that enables us to fit our ecological niche, and do so coherently as a social group. Since in biological terms our mind, emotions and physical sensationsare all the language of a simultaneous, single system, our speech enables us to articulate how this ‘body-mind’, relates to its environment.

I am there, therefore I feel. (At least, I think I can…)

What questions does this allow us to ask about language?

Chomsky suggests that the rules of our language are ‘innate’, arising from our genetics in a predetermined manner, like a body organ. In contrast, the biological evidence, along with Everett’s fieldwork with the Pirahã, suggests instead that the physical structure of our vocal tract, our fine motor control, and our capacities to think in sequences and in symbolic ideas arose as a whole integrated body-mind system.

This combined set of characteristics provided the proto-language function which became refined over evolutionary time into our current communication capacity. This speaking capacity enabled our ancestors to transmit information and behaviours culturally, without directly involving our genetics. Our language function allows us to quickly and flexibly adapt our behaviour to our circumstances.

So: Darwin: 1, Chomsky: 0?

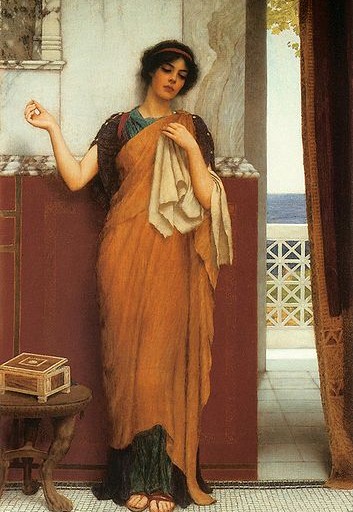

Idle thoughts by John Willam Godward, 1898; Leicester Museum and Art Gallery. Human language makes possible an internal ‘self-talk’ (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

There is however an ‘innate organ’ in the body that makes structured language possible; our brain. It enables us to receive and process our sensory experiences, think intentionally, connect meaning to objects, link ideas, and evaluate memories. To use language, we must be able to perform these cognitive actions, although they are not exclusive to our ability to speak.

Our consciousness allows us to build an internal world in which we use language to define what we think, and to direct these thoughts towards others and back to ourselves. And in this integrated view, where our inner ‘self-talk’ and outer shared speech are part of the same process, Noam Chomsky’s idea of language as a universal innate human mechanism seems to find a home.

Perhaps: Darwin: 1, Chomsky + Darwin = >1

What are we able to say to ourselves about language?

The legend of the ‘Tower of Babel’ portrays the diversity of human languages as a curse. Yet each language is a cultural expression of values, arising in a specific context and anchoring its speakers into a set of attitudes and behaviours which adapt them to their environment. Around the globe, our ecological settings are varied and diverse. According to Daniel Everett, our cultural habits and traditions, transmitted through language, collectively ‘fit’ us to this local ecology with exquisite precision. In evolutionary survival terms, this is a huge strength.

Construction of the Tower of Babel (painted 1604 by Abel Grimmer). The tower of Babel is the focus of a story from the book of Genesis (from the Jewish scriptures and Christian Old Testament). According to this story, t... morehe people of earth sought to ‘make a name for themselves’ by building a great city with a tower right up to heaven. Their God considered this as giving the people too much power, so inflicted a ‘confusion of tongues’ upon them, thanks to which they began to speak different languages and scattered across the earth (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

So what can we say about language?

– It is at once physical and embodied, yet held outside of ourselves in our culture. It is symbolic, emotional, moving, fixed into iconic forms, generalised, specific, and allows us to articulate our internal and external awareness.

– Its form and content, rules and structures are mimicked and learned, yet are also dynamic, constantly being revised and re-drafted as we interact with each other.

– It has evolved through our biology, and is still evolving, remodelling itself to each location, age and culture, whilst holding ideas steady and focussing and fixing our thoughts on specific details.

– It is the way we both define our understanding and code meanings. It is made possible by the way in which we break out of old ways of understanding and find new meanings.

– It uses physical movement to transmit information and reveal feelings and emotions. Observing these movements re-creates that other speakers’ reality in the body-mind of the listener.

– It can adapt itself to any channel, transmitting messages through tones, gestures, syllables, drum rhythms, dots and dashes, touch, or written words.

– It has enabled us to adapt our collective behaviour to fit almost every habitat on earth, and continues to be the means by which we organise ourselves to collectively expand beyond our current limits.

In short, language is a cultural tool, made by us and moulded to our needs. It unites us as a species, and is a vehicle through which we express our uniqueness and diversity. And it enables us to tell ourselves the greatest story ever told.

Our story.

Text copyright © 2015 Mags Leighton. All rights reserved.

References

Cavalli-Sforza, L.L. (1994) The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton University Press.

Chomsky, N. (1957) Syntactic Structures. Mouton de Gruyer.

Chomsky, N. (2009, 18th August); live interview.

Corballis, M.C. (2009) The evolution of language. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences1156, 19-43.

Corballis, M.C. (2010) Mirror neurons and the evolution of language. Brain & Language 112, 25-35.

Desmond, J. (1997) Embodying difference; issues in dance and cultural studies In Meaning in Motion: New Cultural Studies of Dance (J. Desmond, ed.), pp. 29-54 Duke University Press.

Dunn, M. et al. (2011) Evolved structure of language shows lineage-specific trends in word-order universals. Nature 473, 79–82.

Everett, D. (2008) Don’t sleep, there are snakes. Profile Books Ltd.

Everett, D. (2012, paperback edition 2013) Language, the cultural tool. Profile Books Ltd.

Everett, D. (2012) There’s no such thing as universal grammar – interview by Robert McCrum for the Observer Newspaper, 25th March 2012.

Fitch, W.T. (2010) The Evolution of Language. Cambridge University Press.

Ghazanfar, A.A. (2013) Multisensory vocal communication in primates and the evolution of rhythmic speech. Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology 67, 1441-1448.

Greenberg, J.H. (1963) Some Universals of Grammar with Particular Reference to the Order of Meaningful Elements In Universals of Grammar ( J.H. Greenberg, ed.) pp. 73–113. MIT Press.

Hauser, M., Chomsky, N., and Fitch, T. (2002) The faculty of language: what is it, who has it, and how did it evolve. Science 198, 1569-79.

King, S.L. and Janik, V.M. (2013) Bottlenose dolphins can use learned vocal labels to address each other. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 110, 13216-13221.

Levinson, S. and Evans, N. (2010) The myth of language universals; language diversity and its importance for cognitive science. Behavioural and Brain Sciences 32, 429-448.

Lieberman, P. (1998) Eve Spoke; Human Language and Human Evolution. Norton.

Lieberman, P. (2006) Towards an evolutionary biology of language. Harvard University Press.

MacNeilage, P. (2006) The Origin of Speech. Oxford University Press.

Smith, E.A. (2010) Communication and collective action; language and the evolution of human cooperation. Evolution and Human Behaviour 31, 231-245.

Suddendorf, T. and Corballis, M.C. (2007) The evolution of foresight: what is mental time travel, and is it unique to humans? Behavioral and Brain Sciences 30, 299-351.

Tomlin, R. (1986) Basic Word Order: Functional Principles. Croom Helm.