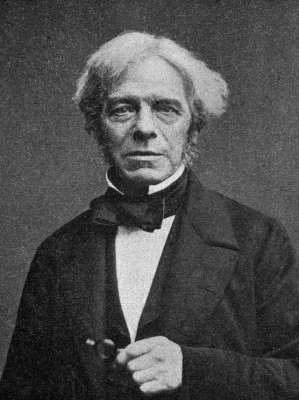

Photograph of Michael Faraday taken in the 1860s by John Watkins. Watkins was known for his portrait photographs of high-profile individuals (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

Michael Faraday (1791-1867) stands out as one of the most influential of scientists. His career began as a chemist but it is his work in physics, particularly electromagnetism, where he made his greatest scientific contributions, opening the doors to the age of electricity. Faraday was also one of the founders of electrochemistry, an area of research which seeks to understand the interplay between electricity and chemical reactions. Faraday was a man of high morals and he strongly believed in the importance of communicating science to the general public. He established the renowned Royal Institution Christmas Lectures in 1825, and these have continued in different guises to this present day.

Faraday’s journey into science reads like a work of fiction; the tale of a gifted underdog who through hard work, imagination, dedication, and an insatiable sense of curiosity for how the world works, overcame overwhelming odds to become one of the world’s greatest scientists. But this is not fiction, it is a true story, and is all the more inspirational for it.

Faraday came from a poor background, which in the world of nineteenth century England stacked the odds against anyone hoping to pursue a scientific career. In order to help support his family Faraday left school at the age of 13 to take a job as an errand boy for a local bookshop, run by one Georg Riebau. This became the initial rung of the ladder in Faraday’s scientific career and the first in a series of serendipitous events. Faraday’s hard work impressed his employer who promoted him to apprentice bookbinder. This opened up a new world to the young Faraday, providing him with access to a wealth of information that with his poor background he would otherwise have had no access to.

Faraday spent his free time reading the precious books that all day he had worked to bind. Of all that he read it was science that piqued his interest, particularly chemistry. Although his wages were small, he saved what he could in order to purchase materials that would enable him to replicate and test the experiments and principles that he learnt in the books. So began Faraday’s fondness – and natural ability – for scientific discovery through practical experimentation, something he was encouraged to undertake by Riebau who allowed him to use a space at the back of the bookshop.

In another serendipitous moment, one of Riebau’s customers gave Faraday a ticket to a series of lectures by the chemist and inventor Sir Humphry Davy. At the time Davy was one of the most famous scientists in England and Faraday took detailed notes at the lectures. These he later bound and sent to Davy as a token of respect. This act of veneration was to have fortuitous ramifications for the young Faraday; when Davy was injured in an experiment that impeded his ability to write, he remembered the impeccable notes that Faraday had sent and contacted him to ask if he would like to serve as his amanuensis for a few days. Faraday jumped at the opportunity and ultimately this led to Davy offering him the position of Chemical Assistant at the Royal Institution in 1813.

Faraday remained with the Royal Institution for the next 54 years. Here he succeeded Davy in 1825 (in the previous year he had been elected to the Royal Society), and in 1833 was made Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution.

Faraday was a prolific scientist and inventor. One could write volumes detailing his many and varied discoveries, but consider a few of his ‘greatest hits’:

– Gas liquefaction (1823). Using mechanical pumps to apply pressure, gases with high critical temperatures such as ammonia can be liquefied. Faraday also observed that when ammonia evaporates it causes its surroundings to cool. This ‘absorption cooling’ is the principle upon which refrigerators work;

– Discovery of benzene (1825). Faraday originally named this chemical compound ‘bicarburet of hydrogen’, and today benzene is used in the manufacture of a wide range of drugs, plastics, and detergents;

– Discovery of electromagnetic induction (1831). When a magnet is moved inside a coil of wire it causes electricity to flow. Accordingly, electricity could be generated by the rotation of magnets rather than by using metal plates and chemical solutions. Most of the electricity we use is a direct result of Faraday’s insight;

– Invention of the ‘Faraday Cage’ (1836), a cage-like structure composed of a metallic mesh which shields its contents from electromagnetic energy by distributing the charge around the exterior of the cage. The Faraday cage has a vast array of applications, from microwave ovens where it restricts the escape of electromagnetic radiation, to purpose-built cages around telecommunications equipment to protect them from lightning strikes;

A Faraday cage in operation. The women inside are perfectly safe because the charge is distributed around the outside of the cage (Image: Antoine Taveneaux/Wikimedia Commons)

– Discovery of the Faraday Effect (1845), the first experimental evidence to show that electromagnetism and light are related. The idea was later developed by the Scottish mathematical physicist James Clerk Maxwell in the 1860s, which established that light is an electromagnetic wave.

Faraday also flags up a common misconception that science and religion are mutually exclusive. In the media today, there is a time-worn formula for presenting the interplay between science and religion. On the one hand we have coverage of extreme religious opinions, whilst on the other hand we have prominent scientists (and comedians) who adopt a vocal atheist stance.

Any topic which presents a conflict of opinion between these two views has become staple ‘news’, but does it represent reality? This over-simplified polarization of views bears little resemblance to day-to-day life, with reality being somewhat more nuanced. Today, as in the past many scientists are atheists, some (like the great biologist Thomas Huxley) are agnostic, whilst others subscribe to a specific faith. For example, Faraday had no doubt of what he thought of as God’s agency in the world. Specifically, he belonged to the Sandemanian denomination which was an offshoot of the Church of Scotland. Nor was he alone. Recall, for example, that Gregor Mendel (the father of genetics) was an Augustinian monk, and Charles Lyell (the father of modern geology) was a devout Christian.

We know that Faraday was one of the world’s finest scientists, but where did he stand upon the subject of evolution? The answer is that we do not know. Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1861, just six years before Faraday’s death. Faraday made no disparaging comments about evolution, but Colin Russell (2000) suggests that his silence on the matter may have been because, like many physical scientists of the time, he dismissed evolution as “only a theory”.

However, one cannot help but wonder how, had Faraday lived longer, he may have reconciled his faith with the ever-growing body of scientific evidence for evolution. For example, Charles Lyell had enormous difficulty reconciling his Christian beliefs with natural selection. Despite this, Lyell and Darwin remained firm friends, happy to discuss their differences with respect and candor; a fitting tribute to the intelligence and open-mindedness of both men.

Faraday was hugely respected within his lifetime and so too the theoretical physicist Albert Einstein held Faraday in enormous esteem as one of his three scientific heroes (the other two being Isaac Newton and James Clerk Maxwell). Regardless of his success and veneration, Faraday remained a man of modesty and firm principles; twice he was offered the presidency of the Royal Society, one of the world’s oldest and most eminent scientific institutions, but on both occasions declined the honour. Faraday had come a long way, and it is worth noting that Joseph Banks, an earlier President, had rejected Faraday’s application for a job as a bottle washer as unworthy of a reply.

Faraday’s expertise in chemistry led the British government to ask him how chemicals could be used against Russia in the Crimean War. Faraday was more than capable of applying his knowledge to develop such weapons, but he found the very notion morally repugnant and refused to assist. Faraday also made a tremendous contribution to the public understanding of science, which included 123 Friday evening public discourses. Similarly, he was keen to apply science to the broader public good and this he did through his work on the efficiency of lighthouses and safety in coal mines. During his life he was offered a final resting place in the company of Kings and Queens at London’s Westminster Abbey, but he respectfully declined, choosing instead to be interred in the more humble surroundings of Highgate Cemetery, London.

Text copyright © 2015 Victoria Ling. All rights reserved.

References

Arianrhod, R. (2005) Einstein's Heroes: Imagining the world through the language of mathematics. Oxford University Press.

Cantor, G. (1991) Michael Faraday: Sandemanian and Scientist. A study of science and religion in the nineteenth century. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ecklund, E.H. and Scheitle, C.P. (2007) Religion among academic scientists: Distinctions, disciplines, and demographics. Social Problems 54, 289-307.

Gooding, D. (1991) Experiment and the Making of Meaning: Human Agency in Scientific Observation and Experiment. Springer.

Gooding, D. and James, F.A.J.L. (eds.) (1985) Faraday Rediscovered: Essays on the Life and Work of Michael Faraday, 1791‐1867. Stockton Press.

Hamilton, J. (2003) Faraday: The Life. HarperCollins.

James, F.A.J.L. (ed.)( 2002) The Common Purposes of Life: Science and Society at the Royal Institution of Great Britain. Ashgate Publishing Limited.

James, F.A.J.L. (2010) Michael Faraday: A very short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Russell, C. A. (2000) Michael Faraday: Physics and faith. Oxford University Press.