A lone singer waits for darkness.

Dusk falls. As the waves push and pull at the sand with a steady rhythm, he revs up his vocal muscles for this, his love song.

He begins to hum. His baritone burr becomes louder and louder, booming across the bay. After a few minutes, another voice joins in, slightly off pitch.

They sing for over an hour. Local residents head indoors, slamming windows to block out the noise.

The male plainfin midshipman fish has evolved to sing; not for ‘fun’ but to attract females to lay their eggs in his rocky burrow. The call advertises his suitability to safeguard first the eggs and later the juvenile fry. We usually associate parental care with mammals and birds. For these territorial nesting fish, protection improves the survival of young at their most vulnerable life stage, which confers a considerable selectable advantage.

Sneaker male fish ‘cuckold’ the parental males. A cuckold is a man with an unfaithful wife, resulting in him bringing up someone else’s offspring. This term comes from the common cuckoo (Cuculus canorus), brood pa... morerasites which substitute their eggs into the nests of other birds. Their eggshell patterns match that of their smaller songbird host, so the surrogate parents (here a reed warbler, Acrocephalus scirpaceus) accept and rear the cuckoo’s outsized offspring (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

However these male fish come in two forms. These other males are smaller, look like females, and like females they don’t sing. When a real female is present they enter the nest and release sperm in the hope of fertilising some of the eggs. Extreme competition for nest sites and breeding partners is thought to have selected for the evolution of these ‘sneaker’ males. Male ‘cross-dressing’ cuckolds have been found in other animal species with extreme between-male competition for mates, some cuttlefish, lizards and dung beetles.

Singing male midshipman fish develop larger and more complex networks of vocal neurons in the brain than non-singers. These networks, together with others that control the sense of hearing, become more sensitive when the levels of sex hormones rise in the fish’ body. These chemicals peak during the spawning season, prompting the males to sing and making the females more responsive.

In some ways the fish brain is a simpler version of our own, and other tetrapods. Studying differences between the brains of these singing and non-singing male fish shows us how mate selection may have first prompted our ancestors to evolve a voice.

How does the male midshipman fish make his song?

The plainfin midshipman is one of several species of vocal fish that nest in the intertidal zone, creating a linear ‘lek’ along the coast. Singing males hum by contracting a pair of sonic muscles attached to the swim bladder. This pressurised air sac, used for buoyancy, shares developmental origins with our lungs and helps the fish amplify his own voice. Fast, synchronised contractions of the sonic muscles vibrate this ‘stiff-walled balloon’, generating sounds.

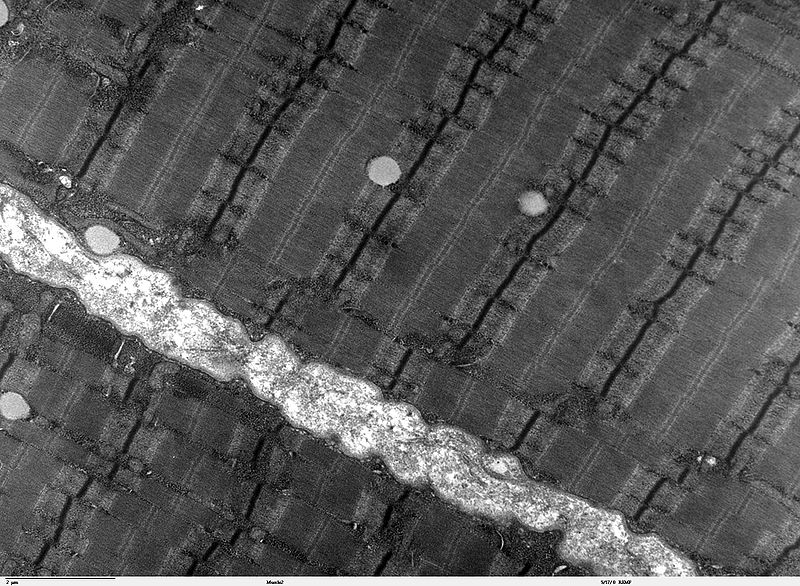

Skeletal muscles appear to have ‘stripes’ of fibres when seen under the microscope. This transmission electron microscope image shows human skeletal muscle fibres close up. The banding patterns visible here results ... morefrom overlapping strands of actin and myosin proteins. Where the actin fibres overlap, they show up as the dark lines under the electron beam, known as Z lines. In plainfin midshipman singing males, the sonic muscle actin fibres overlap more, giving these fibres their unusually high tensile strength, and making the Z lines unusually wide and pronounced (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

All midshipman fish have sonic muscles. In singing males these muscles are six times larger than in females and ‘sneaker’ males. The singer’s muscle fibres are larger, four times as numerous, and surrounded by numerous mitochondria; the cell’s ‘power generators’. Only these powerful muscles and a steady energy supply can sustain their hour-long mating call.

What inspires him to sing?

Singing males call only during the spawning season, and only at night. The hormone melatonin, produced by the pineal gland, regulates this and other daily (circadian) and seasonal rhythms in the physiology and behaviour of vertebrates. Longer hours of daylight in the spring lowers melatonin production, allowing the higher brain centres to release neurotransmitters. These small protein signals trigger the production of sex hormones, which initiate nest building and singing behaviour in midshipman parental males.

A male and female Superb Fairy wren (Malurus cyaneus) from Western Australia. These birds pair-bond to raise their brood, although females often mate covertly with other males (cuckoldry). Male fairy wrens have unusuall... morey large testes (and hence high testosterone levels) for their body size, compared with similarly sized monogamous birds. This pattern is seen in other vertebrates where females mate with several males. Producing more sperm (by having larger testes) significantly affects their chances of breeding success through better sperm competition. ‘Sneaker’ male midshipman fish also have large testes relative to their body size; their limited opportunities to fertilise a female’s eggs means that if they are to succeed, their sperm must be highly competitive (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Both singing and ‘sneaker’ males produce the male hormone testosterone. However singers also produce a related chemical, 11-ketotestosterone, which enhances the performance of the vocal brain’s neural networks, and increases the growth of their sonic muscles.

The larger bodies of these singing males means they take longer to reach reproductive size, but potentially can mate with more females. Sneaker males have the advantage of maturing quickly but the trade-off is that their reproductive success is uncertain.

How is the fish’s brain seasonally rewired for sound?

In singing males, seasonally high levels of 11-ketotestosterone make the vocal parts of the brain more responsive, prompting them to initiate their humming calls. These brain regions contain ‘receptors’; that is protein ‘signal receivers’ that recognise the hormonal messages. As the hormone binds, the receptor changes shape into an active form and in turn modifies the genes which are employed by the vocal neurons to change their function.

A computer generated image of the human androgen receptor protein (coloured spirals) binding to a molecule of testosterone (in white). These signal decoding proteins bind testosterone, and become able to bind to short t... morearget sequences in the DNA. This affects which genes are being copied by the cell into RNA and used to build new proteins. More testosterone makes the fish’s nerve cells more sensitive to signals from other cells, triggering them to ‘fire’ more readily (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

In the part of the female fish’ ear that is the functional equivalent of our cochlea (the human hearing organ), oestrogen hormones are ‘seen’ by receptor proteins in a similar way. This renders her hearing more sensitive within the specific vocal range of the male’s droning call, enabling her to pick up its subtle nuances and high harmonics.

High oestrogen levels are also linked to better hearing in frogs and humans.

Text copyright © 2015 Mags Leighton. All rights reserved.

References

Arch, V.S. and Narins, P.M. (2009) Sexual hearing: the influence of sex hormones on acoustic communication in frogs. Hearing Research 252, 15-20.

Bass, A.H. (1990) Sounds from the intertidal zone: vocalizing fish. Bioscience 40, 249-258.

Bass, A.H. (2008) Steroid dependent plasticity of vocal motor systems: novel insights from a teleost fish. Brain Research Reviews 57, 299-308.

Bass, A.H. et al. (2008) Evolutionary origins for social vocalisation in a vertebrate hindbrain-spinal compartment. Science 321, 417-721.

Bass, A. H. (1996) Shaping brain sexuality. American Scientist 84, 352-363.

Fergus, D.J. and Bass, A.H. (2013) Localization and divergent profiles of estrogen receptors and aromatase in the vocal and auditory networks of a fish with alternative mating tactics. Journal of Comparative Neurology 521, 2850-2869.

Foran, C.M. and Bass, A.H. (1999) Preoptic GnRH and AVT: axes for sexual plasticity in teleost fish. General and Comparative Endocrinology 116, 141-152.

Knapp, R. et al. (1999) Steroid hormones and paternal care in the Plainfin Midshipman fish (Porichthys notatus). Hormones and Behavior 35, 81–89.

Moller, A.P. and Briskie, J.V. (1995) Extra-pair paternity, sperm competition and the evolution of testis size in birds. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology36, 357-365.

Rubow, T.K. and Bass, A.H. (2009) Reproductive and diurnal rhythms regulate vocal motor plasticity in a teleost fish. Journal of Experimental Biology 212, 3252-3262.

Sloglund, C.R. (1961) Functional analysis of swimbladder muscles engaged in sound production of the toadfish. The Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology 10, 187-200.

Wilczynski, W. and Ryan, M.J. (2010) The behavioural neuroscience of anuran social signal processing. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 20, 754-763.