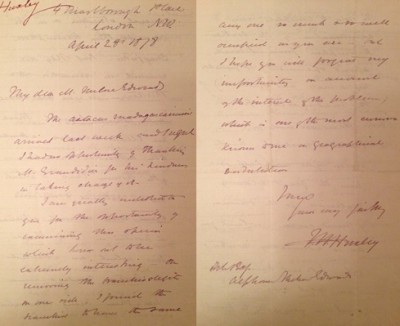

Mary Anning

Portrait of Mary Anning with her dog ‘Tray’. Little is known about the artist of this portrait which in Crispin Tickell’s book Mary Anning of Lyme Regis (1996) is attributed to a ‘Mr Grey’ ... more(Image via Wikimedia Commons)

Mary Anning (1799-1849) was a fossil collector, but unlike the majority of people connected with the study of geology and the history of life in the nineteenth century, she came from a poor background and had little formal education. Regardless, she was self-taught – and highly proficient in – geology and anatomy, and ranks as one of the first, and foremost, of fossil collectors.

Anning was born and raised in Lyme Regis in Dorset, England – a county renowned for its rich fossil yielding sites, and where most of the Jurassic Coast has now been declared a World Heritage Site. Locations such as Black Ven are still popular amongst fossil collectors today. Her father, who was a carpenter, taught Mary how to search for and clean fossils and as a family they would sell these ‘curiosities’ at the seafront. The fossils were popular with the gentry who flocked to this fashionable location in the summer months, and according to Appleby (1979) Anning may have been the inspiration for the tongue-twister She sells seashells on the seashore which was written by the songwriter Terry Sullivan in 1908.

Hugh Torrens (1995) tells us how Anning’s first notable discovery (sometime between 1809 and 1811) was when she uncovered a 5.2 metre long creature which would later be classified as an ichthyosaur. The skull had been discovered by her brother, but it was Anning who located the rest of the skeleton. Although other ichthyosaur fossils had been uncovered both in Dorset and elsewhere, this was the first one to capture the attention of London-based scientists. It was purchased by Henry Hoste Henley, the lord of a local manor and keen fossil collector. He donated it to the naturalist William Bullock for public display in his Museum of Natural History Curiosities in Piccadilly, London. The fossil attracted wide scientific and public interest and through that, Anning became known to the scientific community.

In the early nineteenth century, perceived wisdom was that the Earth was only around 6000 years old and that species did not change through time. As such, this fossil was one key in the scientific debate about the antiquity of the Earth and now vanished species. Beginning in 1814, the surgeon Sir Everard Home wrote a series of six papers on the nature of Anning’s ichthyosaur for the Royal Society. However, not only did Home fail to acknowledge Anning’s painstaking and skilful preparation of the fossil, but in the first paper he mistakenly credited the expertise to William Bullock:

“In the present instance, the pains that have been taken, and the skill which has been exerted in removing the surrounding stone, under the superintendance of Mr. Bullock, in whose Museum of Natural History the specimen is preserved, have brought the parts distinctly into view.” (Home 1814, p.572).

Amongst Anning’s other sensational finds are the first British example of a flying reptile (Pterodactylus macronyx) and the (nearly complete) type specimens of Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus. The last is considered by many to be her greatest discovery; a 2.7 metre long animal with a small head (only 101-127mm in length) but with an extremely long neck. The fossil was described to the Geological Society by the geologist William Conybeare in February 1824. The geologist and palaeontologist William Buckland (1836, p.202) described the find as “..one of the most important additions that Geology has made to comparative anatomy”, yet once again, no credit was afforded to Anning. Despite this, her reputation amongst scientists and lay people alike was already established, and many distinguished visitors came from both home and abroad to meet her in Lyme and even accompany her on tours of the fossil outcrops.

As David Norman (1999) points out, understanding the social texture of a time is important because it provides a deeper appreciation of the work of real pioneers. This is especially true in Anning’s case; her social class excluded her from fully participating in the scientific world of nineteenth century England, dominated as it was by the middle classes, and as a woman she was not eligible to join esteemed societies such as the Geological Society of London (prior to 1918 women were not even permitted to vote in Parliamentary elections in Britain). In addition, Anning came from a family of religious dissenters (meaning they did not follow the Church of England), which at the time meant they were subject to legal discrimination – dissenters were not permitted into a number of professions, could not attend university or join the army.

Anning was not oblivious to the fact that she did not always receive the credit she deserved for her scientific contributions. In a letter referred to by Charles Dickens (1865, p.62), she wrote:

“The world has used me so unkindly, I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone.”

However, Anning’s sharp mind, skill and determination won her the respect of esteemed scientists and public figures alike. For example, the renowned palaeontologist Richard Owen persuaded the British Museum to grant her a pension of 40 pounds per year (a considerable sum in the nineteenth century), and the British Association for the Advancement of Science gave her an annuity. Anning’s discoveries were featured in the lithograph Duria Antiquior, A More Ancient Dorset by the geologist Henry de la Beche. This was the first attempt to illustrate a scene of prehistoric life using evidence from fossil discoveries. In addition, sixteen years after her relatively early death, the leading novelist of the day, Charles Dickens described Anning as a “self-taught geologist” (1865, p.60) who “..won a name for herself, and has deserved to win it.” (1865, p.63).

Duria Antiquior, a watercolour by the geologist Henry de la Beche which depicts life in ancient Dorset based on fossils found by Mary Anning (1830) (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

At the time when Anning began making her remarkable discoveries, scientists were only just beginning to comprehend the nature and antiquity of fossils. Despite the odds being stacked firmly against a lower class, poorly educated woman, her skilful work provided the scientific world with physical evidence that enabled controversial ideas like evolution through natural selection and the antiquity of man ultimately to be investigated, analysed and understood.

As such, Anning can be considered a facilitator of science at one of its most exciting junctures; as pointed out by Goodhue (2005) she played a pivotal role in the development of geology, palaeontology and biology. A fictional account of Anning’s life entitled Remarkable Creatures (2009) was written by Tracy Chevalier and is evocative of this vanished time. Pioneer as she was, one must also acknowledge the extraordinary contributions that amateur collectors continue to make to our understanding of the history of life. Their selfless energy, and not infrequently modest demeanour, should always win the respect and admiration of the professionals.

Text copyright © 2015 Victoria Ling. All rights reserved.

References

Appleby, V. (1979) Ladies with hammers. New Scientist (29 November), 714.

Buckland, W. (1836) Geology and Mineralogy Considered with Reference to Natural Theology (2 vols.). William Pickering.

Chevalier, T. (2009) Remarkable Creatures. Harper.

Conybeare, W. (1824) On the discovery of an almost perfect skeleton of the Plesiosaurus. Transactions of the Geological Society of London 1, 382-389.

Dickens, C. (1865) Mary Anning, the fossil finder. All The Year Round (February 11, 1865), 60-63.

Emling, S. (2009) The Fossil Hunter. Palgrave Macmillan.

Goodhue, T.W. (2005) Mary Anning: the fossilist as exegete. Endeavour 29, 28–32.

Home, E. (1814) Some account of the fossil remains of an animal more nearly allied to fishes than any of the other classes of animals. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 104, 571–577.

Natural History Museum, London. Mary Anning. (Accessed 07.01.2014)

Norman, D.B. (1999) Mary Anning and her times: the discovery of British palaeontology (1820–1850). Trends in Ecology and Evolution 14, 420–421.

Torrens, H. (1995) Mary Anning (1799–1847) of Lyme; 'The Greatest Fossilist the World Ever Knew'. The British Journal for the History of Science 25, 257–284.

![The professional rivalry between Thomas Huxley and Richard Owen was so well known during their time that the writer Charles Kingsley made reference to it in his classic children's book The Water Babies, published in 1863. In this illustration from the 1885 edition, drawn by Linley Sambourne, we see Richard Owen (left) and Thomas Huxley examining a water-baby: "But they would have put it [the water baby] into spirits, or into the Illustrated News, or perhaps cut it into halves, poor dear little thing, and sent one to Professor Owen, and one to Professor Huxley, to see what they would each say about it." (Kingsley, 1889, p.69) (Image by Linley Sambourne via Wikimedia Commons)](http://www.42evolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Water-Babies-400x206.jpg)