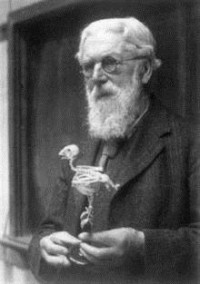

Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov (Image: Library of Congress reproduction number LC-USZ62-118109/Wikimedia Commons)

Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov (1887-1943) was a Russian botanist, geneticist, and agronomist. He was President of the National Geographic Society of the USSR, set up the Department of Genetics at the All-Union Institute of Plant Breeding in what was then Leningrad, and founded what was once the world’s largest collection of plant seeds, collected from every corner of the world.

Vavilov had a contagious enthusiasm for science and his contribution to evolutionary studies was immense, yet he has largely passed under the radar in terms of the wider public and scientific appreciation. Not only have his scientific contributions failed to be given the wider acknowledgement they so readily deserve, but his premature death was shameful; in 1941 he was imprisoned for criticising anti-Mendelian theories that were supported by the Stalin regime, and he died of starvation in the Saratov prison two years later.

Vavilov’s main research interest was in cultivating crops such as wheat and corn in order to tackle famine in Russia and other parts of the world. Specifically, he wanted to use the new science of genetics to breed varieties of crop that not only yielded more grain, but that would also withstand extreme temperatures and be more resistant to insects. As described by Ilya Zakharov (2005), in order for Vavilov to accomplish this goal he needed to overcome two interrelated hurdles. The first was the identification and collection of plant samples from across the globe in order to study and harness their genetic potential. The second was the conservation of the diverse range of wild and domesticated plants in their native setting, the diversity of which Vavilov believed was being eroded as a result of the destruction of natural habitats. Presciently, he spoke about the ‘geography of genes’ and the study of the distribution of genes is now a flourishing area of scientific research, both in plants and animals (including humans).

One of his seminal papers, published in 1912, was in Genetics and Agronomy, where he argued that Mendelian genetics could be used as a basis for the cultivation of plants. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Vavilov made expeditions to 40 countries, spanning five continents in order to collect samples from cultivated plants. This was an immense undertaking, particularly given that many of the countries he visited were politically unstable, making such excursions decidedly risky.

Indeed, for his expedition to Afghanistan in 1924 the Russian Geographic Society awarded him a medal in recognition of his ‘Exploits in Geography’. At the time, his work was widely acknowledged, not only in Russia but across Europe, and just before the First World War he worked in leading laboratories in Britain, France and Germany. Vavilov established the world’s first international seed bank of food plants, containing hundreds of thousands of specimens and preserved within that was the genetic diversity which could be used to breed the high-yield, high-resilience crops which were a test of his hypotheses.

Vavilov was ahead of his time in recognizing the importance of preserving genetic diversity. For example, he identified seven primary centres of origin for the world’s main crops. Centres of origin are geographical areas that have been identified as the original source of specific crop plants. It is from these primary sources that crops were domesticated. The identification and preservation of these regions is essential for the cultivation of crops today because not only are they important sources for the plants’ genes, but highlight areas where biosafety measures should be considered when it comes to introducing genetically modified crops and/or habitats threatened with destruction.

Scientifically, it can be argued that Vavilov’s work on crops and genetic diversity was not only linked to, but also overshadowed, by his profoundly interesting idea of ‘Law of Homologous Series’, first published in the Journal of Genetics in 1922. The starting point was to emphasise the importance of the initial genotype and its subsequent variability. As highlighted by Peter Pringle (2009, p.71): “Darwin was the first to note that similar, sometimes even identical, characteristics arise in animals and plants. On the banks of the River Plate between Uruguay and Argentina, Darwin saw bulldog-faced cows that, because of their jaw, resembled certain breeds of dogs and pigs. But Darwin could take his observation no further because genetics, the science of heredity and variation, did not exist”. Vavilov’s Law of Homologous Series, however, essentially picks up where Darwin left off. To further quote Pringle (2009, p.71):

“Vavilov laid out a simple rule for hunters of crop plants: similar features, such as stem size, and leaf size and shape, could be found in the various evolutionary stages of all closely related species, genera, and even families.”

In 1940 Vavilov was arrested by the ruthless Stalin regime for his criticism of the anti-Mendelian concepts of the Soviet biologist Trofim Lysenko, which happened to be favoured by Stalin. This meant that scientific dissent from Lysenko’s theories, regardless of how absurd Lysenko’s claims may have been, was met with persecution and even a death sentence. Vavilov was sentenced to death in 1941, but in 1942 this was amended to twenty years imprisonment. In 1943 he died in prison of starvation. So great was Lysenko’s political influence that in 1948 the Lenin Academy approved ‘Lysenkoism’ as the accepted direction of biology for the Soviet Union.

Following the death of Stalin in 1953 there was a review of death sentences carried out under his authority, and in 1955 the verdict against Vavilov was rescinded by the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union. Despite increasing criticism from scientists across the globe, Lysenko managed to maintain his powerful position, and it was not until 1965 that he was forced to resign as Director of the Institute of Genetics. Following that, in 1967, the All-Union Institute of Plant Industry was re-named the ‘N.I. Vavilov Institute of Plant Industry’. By this time, Vavilov was considered to be one of the great names in Soviet science. Far too late, but at least some recognition of a great biologist. In the words of Zakharov (2005, p.301):

“The whole life of Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov is a remarkable example of wholehearted devotion to science, to his homeland and to humanity.”

Text copyright © 2015 Victoria Ling. All rights reserved.

References

Crow, J.F. (1993) N.I. Vavilov, Martyr to Genetic Truth. Genetics 134, 1-4.

Crow, J.F. (2001) Plant breeding giants: Burbank, the Artist; Vavilov, the Scientist. Genetics 158,1391–1395.

Pringle, P. (2009) The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov. JR Books.

Tzotzos, G.T., Head, G.P. and Hull, R. (2009) Genetically Modified Plants: Assessing Safety and Managing Risk. Elsevier.

Vavilov, N. I. (1922) The law of homologous series in variation. Journal of Genetics 12, 47-89.

Zakharov, I.A. (2005) Nikolai I Vavilov (1887–1943). Journal of Biosciences 30, 299–301.